A clear and student-friendly explanation of Socrates — his life, the Socratic method, virtue ethics, care of the soul, political views, and legacy. Includes key concepts like Eudaimonia, Ethical Intellectualism, and the unity of virtue, based on Plato’s dialogues.

Table of Contents

Introduction to Socrates

- In the previous lecture, Sophist philosophy was discussed; this section introduces Socrates.

- Unlike most philosophers remembered for their theories or writings, Socrates is remembered mainly for his character and personality.

- Socrates did not write any philosophical texts during his life. It is said he may have written some poems near the end, but none are available to us.

- He has no single fixed theory or system, yet his life and way of questioning deeply influenced philosophy.

- Our knowledge of Socrates comes from the writings of others, not from Socrates himself.

- Key sources include Aristophanes, Xenophon, Plato, and Aristotle.

- Plato is the most important source because he admired Socrates and considered him a guru.

- Plato wrote many dialogues in which Socrates is shown discussing ideas with different people.

- The dialogues are named after the person Socrates is speaking with, such as Crito, Meno, Euthyphro, and Phaedo.

Summary

This section explains that Socrates did not leave any writings, so we know him mainly through the works of others, especially Plato. His influence comes from his life, personality, and dialogue-based way of discussing philosophical questions.

Socrates and Plato’s Dialogues

- Plato wrote all the dialogues about Socrates after Socrates’ death, some of them much later.

- Because of this, it becomes difficult to clearly separate which ideas belong to Socrates and which belong to Plato.

- Plato’s own ideas developed from Socrates’ influence, so sometimes Plato presents his own thoughts in the dialogues under Socrates’ name.

- To solve this issue, scholars divide Plato’s dialogues into three groups:

- Early Dialogues (e.g., Euthyphro, Crito, Apology): These are written close to Socrates’ death and are believed to reflect Socrates’ real views.

- Middle Dialogues (e.g., Meno, Phaedo, Symposium): These contain some of Socrates’ views, but Plato’s own ideas are also mixed in.

- Late Dialogues: Written much later, where Socrates appears less, and Plato presents mostly his own philosophy.

- For understanding Socrates’ true ideas, we will mainly use the dialogues written near the time of his death, and avoid the later ones.

Summary

This section explains the difficulty of separating Socrates’ ideas from Plato’s because Plato wrote about him after his death. To understand Socrates accurately, we rely mostly on Plato’s early dialogues, where Socrates’ own thoughts are believed to appear most clearly.

Early Life and Focus of Socrates

- Socrates was born in 470 BC in Athens, making him the first major Greek philosopher born in that city.

- At that time, Athens was in its Golden Age, a period of cultural and intellectual growth.

- His father was a stonemason and sculptor, and Socrates also worked in the same craft during his early life.

- His mother was a midwife (dai), and later Socrates would metaphorically call himself a “midwife” of ideas — a point that will be explained further.

- Socrates studied the ideas of earlier philosophers like Thales, Pythagoras, Heraclitus, and Parmenides, who focused on understanding nature and reality.

- However, Socrates felt their ideas were very different from each other and lacked a strong foundation, making it unclear which one was correct.

- He questioned the usefulness of such knowledge, asking how knowing the distance of the sun or size of the world would improve practical life.

- Socrates believed knowledge should help humans live better lives, not just describe nature.

- Therefore, he shifted philosophy’s focus to ethical questions: What is right? What is good? What is justice?

Summary

Socrates moved philosophy from studying nature to focusing on how we should live. He emphasized practical knowledge that improves life and centered his questions on ethics and human values.

Socrates’ Unique Personality

- Socrates had a strange and unique personality that was difficult to describe in words.

- He was not physically handsome, yet there was a strong inner attraction and charm in him that made people notice him.

- Xenophon tells a story of a beauty contest between Socrates and Critobulus, who was considered the most handsome man in Athens.

- In the discussion, Socrates asks whether beauty exists only in humans or in many things. Critobulus agrees that many things, like swords, horses, and shields, can be beautiful.

- Socrates then leads Critobulus to see that beauty depends on purpose and function — something is beautiful when it performs its purpose perfectly.

- Using this logic humorously, Socrates argues that his eyes are more beautiful because they can see to the sides, his nose is better because it allows better smelling, and his lips and mouth are better suited to their functions.

- Although everyone still votes Critobulus as more beautiful, the story shows Socrates’ style of questioning and his playful sense of humor.

- The story highlights that Socrates’ true attractiveness was not physical, but came from his mind, character, and engaging way of conversation.

Summary

This section shows that Socrates was not physically good-looking, yet he had a special charm because of his personality and questioning style. Through a humorous dialogue, we see how Socrates used questions to explore ideas and reveal deeper meanings.

Strength and Discipline of Socrates

- Socrates also served many times in the army, where he showed remarkable endurance and strength.

- In Plato’s dialogue Symposium, Alcibiades describes Socrates as someone who could face hardships better than anyone in the army.

- Socrates could live without food and water for several days without difficulty.

- He did not care for drinking wine, but during drinking competitions, he could drink large amounts and still remain completely in control of himself.

- Socrates wore the same simple cloak in every season, whether heat or cold, and he always walked barefoot.

- Even in snow and icy conditions, Socrates walked faster and more comfortably than soldiers wearing shoes.

- Alcibiades also shares a strange incident: one morning Socrates stopped in the middle of a field, lost deep in thought.

- He stood completely still like a statue — the whole day, night, and into the next morning — without moving.

- Only after sunrise did Socrates greet the sun and continue walking, showing his deep mental focus and inner strength.

Summary

This section highlights Socrates’ unusual physical endurance and strong self-discipline. Stories from the army show that his strength came not from the body, but from his calm mind and focused inner life.

Charges and Death of Socrates

- Socrates’ death is considered even more inspiring than his life because it reflects his philosophy in action.

- Only a few philosophers are remembered for a noble death, and Socrates is one of them (the other mentioned is David Hume).

- Just like the conclusion of a book, the final days of Socrates show the essence of his entire philosophy.

- Socrates died in 399 BC at about 70 years of age.

- Two main charges were brought against him:

- Impiety: He was accused of not respecting or believing in the gods of Athens.

- Corrupting the youth: He was accused of influencing young people and making them question traditional beliefs and the Athenian government.

- His trial took place in the Athenian court, where he was found guilty on both charges.

- The court sentenced him to death, and this began the story of his final days.

Summary

This section explains the accusations that led to Socrates’ death. He was charged with disrespecting Athens’ gods and corrupting the youth by encouraging questioning. Found guilty, he was sentenced to death, setting the stage for a significant and meaningful end to his life.

Oracle of Delphi and Wisdom of Socrates

- In Greece, there was a sacred place called the Oracle of Delphi, where the god Apollo was believed to give divine answers.

- A priestess named Pythia spoke these messages, and people from everywhere came to ask questions.

- One day, a friend of Socrates asked the Oracle whether anyone was wiser than Socrates.

- The Oracle replied that no one was wiser than Socrates.

- Socrates was surprised and doubtful when he heard this because he believed he did not have great knowledge.

- To test the Oracle, he began questioning politicians, businessmen, poets, artists, and teachers in Athens.

- He discovered that people who claimed to be wise could not answer basic questions about their own knowledge.

- Socrates realized that these people were ignorant, but they thought they knew everything.

- In contrast, Socrates knew that he did not know, and this awareness of his ignorance made him wiser than others.

- This is why Socrates famously said, “I know that I know nothing.”

Summary

This section explains how the Oracle of Delphi declared Socrates the wisest person. Socrates discovered that true wisdom is recognizing one’s own ignorance, while others falsely believed they already knew everything.

Trial and Search for Truth

- Socrates became completely dedicated to questioning people and searching for true wisdom.

- From morning to evening, he walked around the city, asking questions to anyone considered wise.

- Many young people of Athens followed him, watching how he exposed the false wisdom of respected citizens.

- Because influential people felt insulted and embarrassed by Socrates’ questioning, they began to resent and oppose him.

- This resentment eventually led to the accusations that he insulted Athens’ gods and corrupted the youth.

- Socrates defended himself before a jury of 500 citizens, and his speech is recorded in Plato’s Apology (meaning defense, not apology).

- Despite his clear reasoning, 280 of the votes were against him, and he was sentenced to death by drinking hemlock poison.

- The execution was delayed by a month, so Socrates lived in prison during this time.

- Socrates told the court that even if they forgave him, he would not stop questioning, because searching for truth was the purpose of his life.

- He believed that a life without examining truth is meaningless, and only true knowledge leads to virtue and a happy, meaningful life.

Summary

This section explains how Socrates’ honest search for truth made powerful people angry, leading to his trial and death sentence. Even when facing death, Socrates refused to stop questioning, because for him, truth and knowledge were the foundation of a meaningful life.

Socrates in Prison and His Peaceful Death

- While Socrates was in prison awaiting execution, his friend Crito visited him and offered to help him escape to a safe place.

- Socrates refused to escape. He believed that death is not necessarily a bad thing.

- He explained that if the soul continues after death, then death is good. And if death is only a dreamless sleep, that is also peaceful.

- Socrates said that at his age (over 70), living in hiding would be meaningless, because the true purpose of life is the search for truth.

- He chose to accept death calmly, rather than live without meaning.

- After one month in prison, the final day arrived. A guard gave Socrates a cup of poison (hemlock).

- Socrates drank it in one breath, and the poison slowly spread through his body.

- He faced death peacefully and without fear, showing that his philosophy and his life were one.

- Though his body died, Socrates became immortal in influence, remembered for over 2000 years.

Summary

This section describes Socrates’ final days in prison. He refused to escape, accepted death peacefully, and drank the poison with calm dignity. His death showed the strength of his beliefs and made his legacy everlasting.

Socratic Method and the Search for Truth

- Socrates believed that right action must be based on truth. If we do not know the truth, we should question and examine our opinions.

- He taught that there is a difference between being ignorant and not knowing that you are ignorant.

- He compared ignorance to a disease: knowing you are ill allows you to seek treatment, but not knowing makes the condition worse.

- For Socrates, ignorance was more harmful than physical disease because it damages the soul and character, not just the body.

- His goal was to help people recognize their ignorance, so they could begin to improve themselves and move toward wisdom.

- To do this, he used a special questioning technique known as the Socratic Method (Socratic Questioning).

- This method works by asking logical, step-by-step questions that reveal contradictions in a person’s beliefs.

- It is also called Elenchus, meaning to logically show when an argument is false.

- Plato later developed this approach further and called it Dialectic — a process of discovering truth through conversation and reasoning.

Summary

This section explains the Socratic Method, a questioning technique used to reveal ignorance and guide people toward truth. Socrates believed that recognizing one’s ignorance is the first step to wisdom and that honest questioning helps improve the soul and leads to a better, more meaningful life.

Socratic Dialogue vs Other Argument Styles

- The Socratic Method (Dialectic) uses a step-by-step question and answer pattern.

- Socrates asks questions based on the other person’s answers, helping the topic become clear and refined over time.

- Eventually, the person realizes that their earlier answers were incorrect or incomplete.

- This method does not always give the final answer, but it helps remove false beliefs and improves understanding.

- Eristics is a different form of argument where the main goal is to win the debate, using rhetoric, emotion, or even weak logic.

- Apologetics is another style where the aim is to defend a belief or idea, especially in religious contexts.

- Dialectic, however, is not about winning or defending. Its goal is to understand a topic deeply and move closer to truth.

Summary

This section explains how the Socratic Method works through questioning to reveal false beliefs and improve understanding. Unlike eristics (which aims to win) or apologetics (which aims to defend), dialectic focuses on discovering deeper truth.

Seven Stages of Socratic Method

- Stage 1 — Finding the issue: In casual conversation, Socrates spots a point with philosophical significance and brings it into focus.

- Stage 2 — Fixing the core term: He centers the talk on a key concept without which the discussion cannot move forward (e.g., “What is love/justice/virtue?”).

- Stage 3 — Declaring ignorance: Socrates says he knows nothing and invites the other (the “wise” person) to give a definition of the chosen term.

- Stage 4 — Gentle examination: After brief praise, he analyzes the definition, asks clarifying questions, and exposes gaps or contradictions.

- Stage 5 — Iterative refinement: The other person revises or replaces the definition; Socrates repeats praise and probing, keeping the cycle going.

- Stage 6 — Realizing ignorance: The person recognizes that they did not truly know; their false confidence is replaced by honest awareness.

- Stage 7 — Two outcomes: Either the person escapes with excuses, or they accept their ignorance, opening the way to genuine learning.

Summary

These parts outline seven clear steps in the Socratic method: identify a live issue, fix a core term, invite a definition, examine it, refine through repetition, realize ignorance, and finally either flee or accept the truth. The sequence cleans out false opinions and prepares the mind for real understanding.

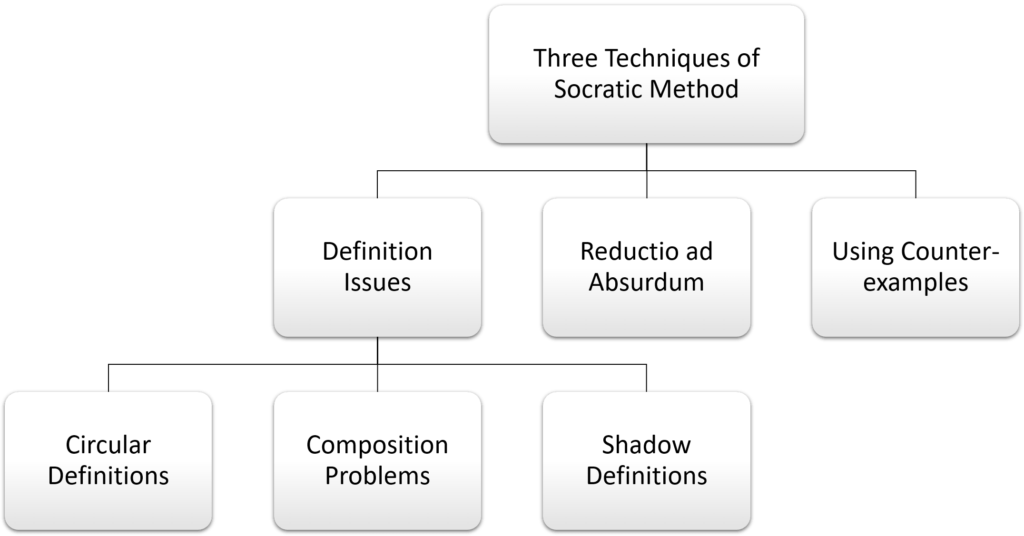

Technique 1A: Problem of Circular Definitions

- In the Socratic Method, three main techniques are used to question and refine ideas. The first technique focuses on attacking or testing the definition given by the other person.

- Socrates shows that many definitions appear correct, but actually fail logically when examined closely.

- One common problem is the circular definition, where the explanation simply repeats the same idea without giving real meaning.

- Example of Circular Definition:

- If someone defines courage as “what courageous people do,” the definition becomes circular.

- “Courage is what courageous people do” and “Courageous people do courage” tells us nothing new.

- Circular definitions work like going in a loop:

- “My house is in front of the temple.”

- “Where is the temple?”

- “In front of my house.”

- Such definitions do not clarify the concept, they just move in circles.

- Many everyday definitions are circular:

- Justice = acting justly.

- Knowledge = what knowledgeable people have.

- Friendship = what exists between friends.

- A leader = someone who leads.

Summary

This part explains the first technique of the Socratic Method, where Socrates examines definitions to reveal problems such as circular meaning. A circular definition repeats the same idea without explaining it, helping Socrates show that the other person has not truly understood the concept.

Technique 1B: Composition Problem in Definitions

- The second issue in definitions is called the composition problem.

- This happens when someone tries to define a smaller part (a specific concept) by using a larger whole that contains many different elements.

- For example, if Socrates asks “What is justice?” and the person answers “Justice is virtue,” the answer is too broad.

- Virtue is a large category that includes many qualities such as courage, wisdom, kindness, honesty, etc.

- Justice is only one part within this larger category, so defining justice as virtue does not actually explain what makes justice unique.

- Just because justice belongs to the group of virtues, it does not share all the same properties as every other virtue.

- Example: A penguin is a bird, but not all qualities of birds apply to penguins (penguins cannot fly like pigeons).

- So defining justice simply as virtue is like defining a penguin simply as a bird — the definition is too general and does not clarify the specific concept.

Summary

This technique shows how some definitions fail because they use a very broad category to define a specific idea. When a part is explained only in terms of the whole, the definition becomes unclear, and the unique nature of the concept remains unexplained.

Technique 1C: Shadow Example (Confusing Example with Definition)

- The third issue in definitions is when a person gives examples instead of an actual definition. This is called the shadow example problem.

- When asked “What is a rectangle?”, simply pointing to a book, mobile screen, or tablet does not define a rectangle; these are just examples.

- A real definition must explain the conditions or criteria that make something a rectangle:

A rectangle is a shape with four sides and four right angles (90° each). - The same logic applies to other concepts:

- Saying “This person is a vegetarian” is not a definition of vegetarian.

- The definition should explain the principle, for example:

A vegetarian is someone who does not eat meat.

- Examples show the concept, but a definition explains the concept.

- Socrates wants precise definitions, not just instances.

- Therefore, when testing a definition, Socrates checks:

- Is it circular?

- Is it too broad (composition problem)?

- Is it merely an example instead of a true definition?

Summary

This technique shows that giving examples is not the same as giving a definition. Socrates tests whether a person is explaining the concept itself, or only pointing to things that represent it. A clear definition must describe the essential features that make something what it is.

Technique 2: Reductio ad Absurdum (Reducing to Absurdity)

- In the second technique, Socrates uses a logical strategy called reductio ad absurdum, meaning “reducing an argument to a contradiction or absurd conclusion.”

- This method begins by accepting the other person’s definition as true, without arguing against it directly.

- Then, using the person’s own statement, Socrates draws out a logical conclusion that is clearly absurd, impossible, or self-contradictory.

- Once the absurd result appears, it proves that the original definition or belief must be false or incomplete.

- Example from Plato’s Republic:

- Thrasymachus defines justice as:

“Justice means working for the advantage of the stronger (the ruler).” - Socrates accepts this definition for the sake of argument.

- Then he asks: What if the ruler makes a law by mistake that harms himself instead of benefiting him?

- If people follow this harmful law, they are no longer working for the ruler’s advantage — which means, according to the definition, they are being unjust even though they are obeying the law.

- Thrasymachus defines justice as:

- This leads to a contradiction:

- The definition says obeying rulers is justice.

- But the same definition says obeying can also be injustice.

- Therefore, the original definition becomes absurd, and it collapses under its own logic.

Summary

This part explains the reductio ad absurdum technique: Socrates accepts an opponent’s idea temporarily, then uses reasoning to show that it leads to a contradiction. Once an argument leads to something impossible or absurd, it proves the original idea was flawed.

Reductio ad Absurdum: More Examples

- This stage shows how Socrates uses reductio ad absurdum by accepting a definition as true, then showing that it leads to contradictory or impossible results.

- In Euthyphro, the concept being defined is piety (devotion or respectful action towards the gods).

- Euthyphro defines piety as: “Piety is what the gods love.”

- Socrates then asks whether the gods always agree with each other. Euthyphro admits that gods often disagree and argue.

- This means one god might approve of an action while another god might disapprove of the same action.

- Therefore, the same action would be pious and not pious at the same time — which is impossible.

- So the definition fails, because it produces a contradiction.

- Another example: Someone says “Justice means returning what you borrowed.”

- Socrates accepts this temporarily.

- He asks: If you borrowed a weapon from a friend who is now mentally unstable, should you return it?

- Returning it could harm people, so returning it cannot always be justice.

- Therefore, this definition also leads to an absurd result and must be corrected.

Summary

This section shows how Socrates proves a definition wrong by accepting it for the moment and pushing it to a point where it becomes contradictory. When an idea leads to an impossible or harmful conclusion, it shows the original definition was incomplete or incorrect.

Technique 3: Using Counterexamples

- The third technique Socrates uses is giving a counterexample to test whether a definition works in all cases.

- A good definition must be universally true; if even one exception is found, the definition needs to be corrected.

- In Meno, Meno says: “A virtuous person is the one who can rule or govern.”

- Socrates then provides two counterexamples:

- A virtuous child cannot rule, yet we still call the child good.

- A cruel tyrant can rule, yet we would never call him virtuous.

- These counterexamples break the definition because it wrongly includes tyrants and excludes virtuous children.

- A counterexample works the same way in everyday life:

- If someone says, “All birds can fly,” you can mention the penguin.

- If someone says, “All fruits are sweet,” you can mention the lemon.

- Through counterexamples, Socrates shows that many definitions look correct at first, but fail when tested with real cases.

- Socrates chooses counterexamples carefully, like a skilled chess player who always anticipates the opponent’s next move.

Summary

This section explains how Socrates uses counterexamples to test whether a definition is universally true. If even one real-life case does not fit the definition, the definition must be revised. This simple but powerful technique helps expose unclear or incomplete ideas.

Socrates on Knowledge and Universal Concepts

- Epistemology means the theory of knowledge—how we know what we know.

- According to Aristotle, Socrates’ greatest contributions to knowledge were:

- Inductive reasoning (moving from many examples to a general concept).

- Universal definitions (finding the unchanging core meaning of a term).

- Socrates believed that behind many different examples of a thing, there is one common concept that makes them all belong to the same category.

- For example, many things can be beautiful: a flower, music, a cloud, a painting, or a mathematical equation.

All of these are very different, yet something common in them makes them beautiful. - That common factor is the universal concept of beauty.

- So we must distinguish between:

- Example (Particular): An individual thing (flower, song, painting).

- Concept (Universal): The essential meaning that never changes (beauty).

- Particulars change and fade:

- A beautiful flower will eventually wither and lose its beauty.

- But the universal concept (beauty itself) never changes and does not decay.

- Therefore, when Socrates asks questions like What is justice? virtue? friendship? love?, he is searching for the unchanging universal definition, not examples.

Summary

Socrates taught that real knowledge is knowing the universal concept behind many changing examples. Flowers may fade, but the concept of beauty does not. His goal was to define universal ideas like justice or virtue that stay constant, even though their examples in the world keep changing.

Inductive Reasoning and Universal Definition

- To find a universal definition, Socrates used inductive reasoning.

- Inductive reasoning means observing many particular cases and identifying the common quality shared by all of them.

- For example, if we observe many good actions, and see what they all share, we can begin to understand what goodness itself means.

- Particular actions and events change, but the universal concept (like goodness, beauty, virtue) remains constant.

- A universal definition expresses this constant essence.

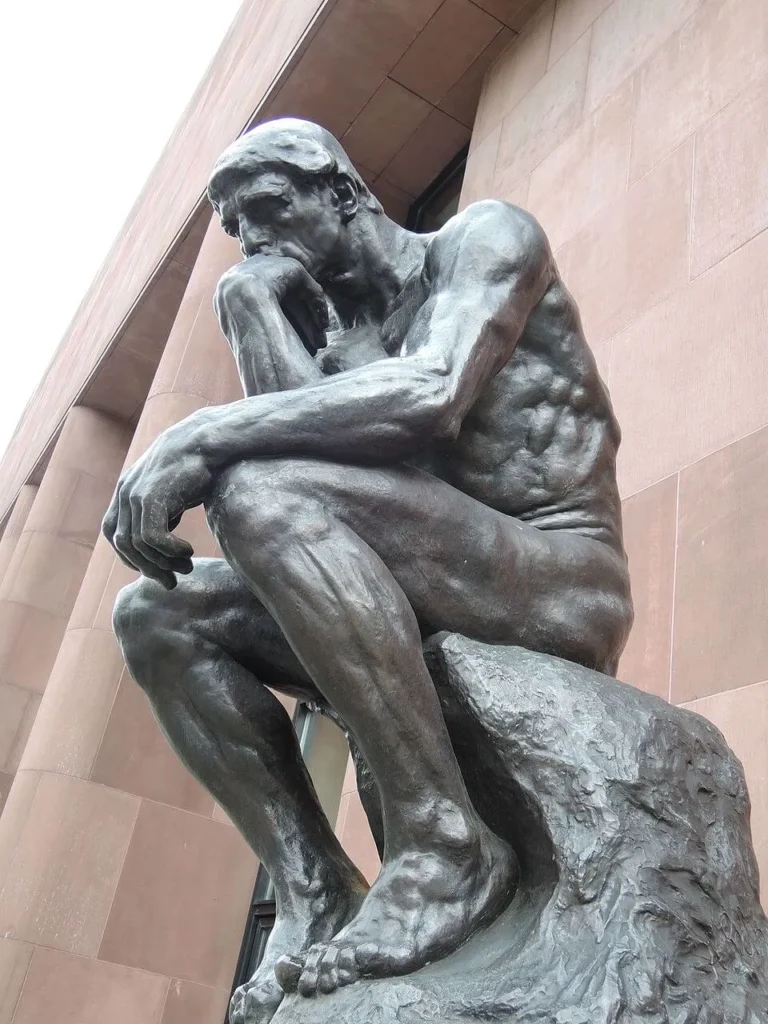

Example: The definition of a human is “a rational animal.” All humans share rationality, even though individuals differ. - Induction is the method, and the definition is the result:

- First, observe many particular examples.

- Then, identify the one common essence.

- The famous statue “The Thinker” symbolizes this idea:

- The figure is naked, showing the animal aspect of humans.

- The figure is thinking, showing the rational aspect of humans.

- This reflects Socrates’ view that a human is both biological (animal) and intellectual (rational).

Summary

This section explains how Socrates used inductive reasoning to form universal definitions. By studying many examples and finding what they share, he identified stable concepts like goodness or beauty. Induction is the process, and the universal definition is the final insight into the true essence of a concept.

Importance of Clear Concepts in Knowledge

- Some may wonder why Socrates spent so much time defining concepts. The reason is that clear concepts are the foundation of all knowledge.

- Just as mathematics depends on precise definitions (point, line, circle, triangle), all forms of knowledge depend on accurately defined ideas.

- The accuracy of our knowledge depends on how precise our basic concepts are.

- If the core concepts are unclear, then the whole system of knowledge built on them becomes weak and confused.

- In science, we use concepts like cause, change, motion, speed, mass, and energy to explain nature and reality.

- When we observe many events where one thing influences another, we form the concept of causation — a universal idea drawn from many particular cases.

- A scientific theory like E = mc² depends on understanding its concepts (energy, mass, speed of light, vacuum). Without clear definitions, the theory cannot be understood.

- By Aristotle’s time, more than 50 major concepts had been clearly defined to develop science, mathematics, and philosophy.

- Socrates realized that just as these concepts help us understand nature, we also need clear concepts to understand human life.

- Therefore, he focused on defining virtue, justice, goodness, happiness, and friendship — the building blocks for understanding how to live well.

Summary

This section explains why Socrates emphasized clear and precise definitions. Just like science and mathematics rely on well-defined concepts, understanding human life and behavior requires clear ideas like virtue, justice, and goodness. Strong concepts create strong knowledge; unclear concepts lead to confusion.

Development of Concepts and Their Independence

- As discussions continued, philosophers began to define concepts more clearly and also developed the basic laws of logic.

- Concepts act like bricks, and logic acts like cement; together they form the structure of knowledge.

- Some thinkers noticed that examples can disappear, but the concept itself remains.

- A beautiful flower may wither, but the concept of beauty does not disappear.

- This suggests that beauty exists independently of any single object.

- There are also concepts that are perfect in definition but have no perfect example in the real world.

- Example: A line in geometry is defined as one-dimensional, having only length and no width.

- But any line we draw with pencil or marker will always have some width, so no physical line matches the perfect concept.

- Therefore, concepts can be:

- Independent of the objects that display them.

- More perfect than any real example we can observe.

- Later thinkers, especially Plato, began to argue that these perfect concepts exist as independent Forms or Ideas in reality.

- Socrates himself did not claim these Forms existed separately, but after him, many philosophers believed they did — this idea will be explored in Plato’s discussions.

Summary

This section explains that concepts are more stable and perfect than their real examples. A flower may die, but beauty remains; a perfect line exists only as an idea. These observations led later philosophers, especially Plato, to believe that universal concepts exist independently as Forms.

Socrates as the “Midwife of Ideas”

- Socrates’ mother was a midwife, and Socrates often called himself a midwife of ideas.

- A midwife does not give birth to the baby herself; she only helps the mother deliver it.

Similarly, Socrates said he does not give knowledge, but helps others bring out the knowledge already inside them. - Socrates believed that true knowledge does not come from outside, through the senses like seeing or hearing.

- Instead, knowledge already exists within the soul in a hidden or unawakened form.

- Through questioning (Socratic Method), he helped others discover or remember that knowledge.

- This led to the idea of innate ideas: some truths are inborn, such as basic moral principles, logical rules, or mathematical concepts.

- Later philosophers developed this idea further:

- Plato built a full doctrine of innate knowledge and the soul remembering truths.

- Descartes also supported innate ideas in the mind.

- John Locke, however, rejected this view and argued that the mind is a blank slate (tabula rasa) at birth.

- But for Socrates, wisdom exists inside us, and learning is the process of bringing hidden knowledge into awareness.

Summary

Socrates compared himself to a midwife because he believed that knowledge already exists inside each person. Through questioning, he helped others bring this inner knowledge to light. This became the basis for the philosophical idea of innate ideas, which later influenced Plato and Descartes.

Recollection and Virtue Learning

- Meno asks whether virtue can be taught; Socrates replies that learning is really recollection, realizing knowledge already hidden within.

- To show this, Socrates questions Meno’s slave, who knows Greek but no geometry or mathematics.

- Socrates draws a square on the ground and asks how to make a square double in size; the slave initially says he does not know.

- Through careful, step-by-step questions, the slave discovers that using the diagonal of the original square gives a double-area square.

- Socrates points out he did not teach the method; by reflecting on the questions, the slave recalled the truth already within.

- This example supports Socrates’ view that geometry-like knowledge exists innately and can be brought to light by proper questioning.

- Alongside recollection, Socrates stresses inductive reasoning: observe particular cases, extract the universal concept, and define it precisely.

- With clear definitions, we can categorize ideas and build stronger understanding of virtue, justice, and other concepts.

- The combined approach—induction, precise definition, and innate ideas (recollection)—gave philosophy a powerful push forward.

Summary

Socrates argues that learning is recollection of knowledge already within the soul. By questioning Meno’s slave about doubling a square, he shows how truth emerges without direct teaching. This supports his broader method: use induction to find universals, define them clearly, and awaken hidden knowledge.

Note: The doctrine that knowledge is recollection is more likely Plato’s own idea, expressed through the character of Socrates in the dialogue Meno.

Socrates on Soul and Reality

- Socrates did not focus much on metaphysics (ultimate reality questions), because he believed knowing such things does not necessarily improve how we live.

- However, from his discussions, we learn that he placed great importance on the soul.

- Socrates taught that the main purpose of life is to care for and improve the soul, preventing it from becoming corrupted by ignorance.

- He said even if a person has only one day left to live, that day should be spent improving the soul, because we must live with our own character until the end.

- Before Socrates, Greek thinkers saw the soul as secondary, like the air inside a ball — useful, but not the real person.

- Socrates reverses this view: for him, the soul is the real person, and the body is only a temporary instrument or vehicle.

- He compared the soul to a driver and the body to a car: the driver is what truly matters.

- Caring only for the body and ignoring the soul is like polishing shoes every day while ignoring the injured foot inside them.

- Whether Socrates believed in the immortality of the soul is not completely clear, but some statements suggest that he did believe the soul continues after death.

- For example, in his final days, when Crito asked how to bury him, Socrates replied that they could bury the body however they wished — but they would not be able to “catch” him, implying the soul remains beyond the body.

Summary

This section explains Socrates’ view that the soul is the true self, while the body is only temporary. The most important task in life is to care for and improve the soul. Socrates likely believed that the soul continues after death, as suggested by his calm attitude in his final moments.

Note: It is unclear whether Socrates believed soul is immortal.

Socrates’ Ethics and the Question of Living Well

- For Socrates, the central question of philosophy is: How should a person live?

- He lived through both peace and war, seeing Athens in its Golden Age and during its conflict with Sparta.

- Because he experienced real life closely, he believed metaphysical questions (like how the world was created) cannot solve actual human problems.

- Socrates shifted philosophy’s focus from the universe to human life, making ethics the center of philosophy.

- The key Greek term here is Arete, meaning excellence or living at your best.

- Every object has a purpose; if it performs its purpose perfectly, it achieves excellence (Arete).

Example: A knife’s excellence is in cutting well. - Similarly, human excellence means living life well and meaningfully.

- A human life is meaningful when we live in alignment with our true purpose, rather than just surviving or seeking pleasure.

- Therefore, for Socrates, the goal of life is to achieve excellence (Arete) by developing our character and improving our soul.

Summary

Socrates placed ethics at the center of philosophy, asking how one should live. He taught that excellence (Arete) means fulfilling the purpose of one’s existence. For humans, this excellence lies in living wisely, improving the soul, and shaping a meaningful life.

Virtue and the Goal of Life (Eudaimonia)

- Many people do not consider Socrates’ question “How should one live?” to be important.

- Some believe they have no choice in life (like slaves or those who simply follow circumstances), so they never reflect on how to live well.

- Others believe they have choice, but simply imitate society, chasing money, status, and pleasure because they see everyone else doing the same.

- Socrates rejects both approaches. He says that a person should live a virtuous life.

- A virtuous life is the best life, because it fulfills the true purpose of human existence.

- Socrates uses the Greek term Eudaimonia, meaning ultimate well-being, deep happiness, or a life of flourishing.

- Eudaimonia is not temporary pleasure or a moment of feeling good. It refers to the quality of one’s entire life.

- A person cannot say, “I lived well for five minutes.” Good living must be continuous, shaping the whole life.

- According to Socrates, the ultimate goal of human life is to achieve Eudaimonia.

- And this ultimate happiness can only be achieved through virtue.

Summary

This section explains that the best life is a virtuous life, because virtue leads to Eudaimonia—a deep, lasting state of well-being and fulfillment. Unlike temporary pleasure, Eudaimonia defines the entire life and is the ultimate purpose of human existence according to Socrates.

Virtue as Knowledge (Ethical Intellectualism)

- Socrates said that virtue is a form of applied knowledge, called techne in Greek (the root of the word technology).

- Just as a good doctor understands diseases, patients, and medicines, and a good shoemaker understands shoes completely, a virtuous person understands human nature and the essence of the good life.

- To live a good life, we must first understand what ‘goodness’ means.

This deep understanding of goodness is what Socrates calls virtue. - For Socrates, virtue and knowledge are the same.

If you know what is truly good, you will naturally act in the right way. - This view is called Ethical Intellectualism — the idea that morality comes from knowledge.

- According to Socrates, people do wrong only because they lack knowledge of what is truly good.

- No one knowingly chooses to do wrong.

If someone acts wrongly, it is because they are ignorant, confused about life’s true goal. - For example, someone may chase money as the highest goal and commit harmful acts to achieve it — not because they are purposely evil, but because they are mistaken about what happiness really is.

- Celebrities or influencers who promote harmful things for money also believe (incorrectly) that money is life’s ultimate goal. Their wrong actions come from wrong understanding, not intentional evil.

Summary

This section explains that for Socrates, virtue means true knowledge of what is good. If a person genuinely understands goodness, they will act rightly. Wrong actions come from ignorance, not intention. Therefore, the path to a good life is to gain wisdom about the real purpose of life, not to chase temporary goals like money or popularity.

Criticism of Socrates’ View of Virtue and Knowledge

- Many philosophers, including Aristotle, disagreed with Socrates’ claim that virtue = knowledge.

- Critics argue that sometimes we know what is right, but still fail to do it.

- Example: A smoker knows smoking is harmful, yet continues.

- We know scrolling reels wastes time, yet we keep doing it.

- Critics say the problem is not knowledge, but willpower.

The intellect may understand the good, but the will and desires may still pull us in the opposite direction. - They highlight the difference between knowing the good and doing the good.

- However, Socrates responds that the real issue is not weak will, but incomplete knowledge.

- According to Socrates, when someone chooses the wrong action, they are thinking in a short-term way.

- They choose instant pleasure over long-term well-being because they do not clearly understand the long-term consequences.

- If a person truly understood — with full awareness — that option X is better than option Y, they would never choose Y.

- Therefore, wrong action happens because a person’s understanding is partial and shallow, not because their will is weak.

Summary

This section explains that although critics say we sometimes fail to do what we know is right, Socrates argues that such failure comes from shallow, short-term thinking, not lack of willpower. For Socrates, if we truly understand the good in a deep and full way, we will naturally choose it. Virtue remains rooted in clear and complete knowledge.

True Knowledge and the Examined Life

- Socrates can say that if we accurately compare the short-term pleasure and long-term harm of a bad habit, we will naturally stop the habit.

- When understanding is clear and complete, we do not need willpower to act correctly.

- We can compare this to seeing a snake: as soon as we see it, we instantly jump aside. Knowledge and action happen together, with no gap.

- Socrates is not talking about information (like motivational quotes or self-help advice). Information does not create lasting change.

- Real knowledge (wisdom) is direct, living understanding — like touching fire and immediately knowing it burns.

- This kind of wisdom changes behavior naturally, without effort.

- To reach this wisdom, Socrates says we must continuously examine:

- Our life

- Our actions

- Our beliefs

- Our assumptions

- Socrates famously said: “The unexamined life is not worth living.”

- Therefore, we must question concepts like:

- virtue

- courage

- justice

- happiness

- beauty

and refine our understanding every day.

Summary

Socrates teaches that real wisdom leads directly to right action. It is deeper than information—it is lived understanding. To achieve this wisdom, we must examine our beliefs and decisions daily. The examined life is the only life that leads to true growth and meaningful change.

Caring for the Soul and True Harm

- For Socrates, soul does not mean a ghost.

It means your inner character — the core of your personality. - The most important task in life is to take care of the soul and prevent it from becoming corrupt.

- In Socrates’ time (as in today), most people cared more about money, social status, and image than about character.

- A virtuous person not only improves their own soul but also helps others become virtuous.

Therefore, Socrates questioned both himself and others — he saw this as a moral responsibility. - According to Socrates, external problems (prison, illness, poverty, insult, failure) can harm the body, but cannot harm the soul.

- The only real harm in life is moral corruption — losing honesty, goodness, courage, or integrity.

- He says even in extreme situations, like being unjustly punished, the victim does not suffer the deepest harm.

- The true harm is suffered by the one who commits injustice, because their soul becomes corrupted.

- Therefore, suffering injustice is less damaging than doing injustice.

Summary

Socrates teaches that the soul (character) is more important than wealth, power, or the body. External problems cannot truly harm us; only moral corruption can. A person who does wrong damages themselves more deeply than the one who suffers the wrong. The highest duty in life is to protect and improve the soul.

The Unity of Virtue

- In Plato’s Republic, Polemarchus claims that virtue means helping friends and harming enemies.

- Socrates disagrees, saying true virtue never harms anyone.

Instead, a virtuous person tries to improve others, whether friend or enemy. - Socrates proposes the idea of the unity of virtue: virtues like wisdom, courage, temperance (self-control), and justice are not separate — they are different expressions of the same inner excellence.

- He explains this by examining opposites:

- Both wisdom and temperance have the same opposite: folly (ignorance, foolishness).

- If two virtues share the same opposite, it suggests they are connected at a deeper level.

- Socrates also says that any ability or quality becomes harmful without virtue:

- Wealth without virtue can lead to addiction, greed, or waste.

- Strength without virtue can lead to violence or arrogance.

- Skills and intelligence without virtue can be used for manipulation or harm.

- Therefore, virtue (true knowledge of good) is what makes all other qualities useful and meaningful.

- Without virtue, any ability can become destructive, even to the person who possesses it.

Summary

Socrates teaches that all virtues are ultimately one unified inner quality, rooted in true wisdom. Without this virtue, wealth, power, strength, or skill become dangerous and self-destructive. True virtue helps rather than harms, aiming to improve the character of everyone, including one’s enemies.

Socrates on Politics and Justice

- Socrates did not support democracy because he believed governing requires special knowledge, not the opinion of the crowd.

- He compares it to medicine: we don’t decide which medicine to take by voting, we go to a doctor who understands health.

Similarly, running a state should be done by those with knowledge of governance, not by uninformed majority voting. - When Crito suggests escaping from jail, Socrates refuses. He says:

- If a person disagrees with a law, they should try to change it legally.

- And if change is not possible, they should leave the state, not break the law.

- Doing wrong in response to wrong is still wrong.

Socrates says: two injustices do not create justice. - Breaking laws out of anger or revenge corrupts the soul, and for Socrates, the soul is more important than life itself.

- Socrates states that the true challenge in life is not avoiding death, but avoiding injustice and moral corruption: “The difficulty, my friends, is not to avoid death, but to avoid unrighteousness, for unrighteousness runs faster than death.”

- Death happens only once, on one day of life — but we live with our character every day.

- Therefore, the real purpose of life is to protect and develop the soul, not to fear death.

Summary

Socrates believed that government should be guided by knowledge, not majority opinion. He refused to escape from jail because committing injustice harms the soul, which is more serious than death. For Socrates, avoiding moral corruption is the highest priority; a virtuous life is more important than life itself.

Early Ideas of Social Contract and Natural Law

- Socrates’ ideas contain the early seeds of two major political theories that became famous much later.

1. Social Contract Theory

- This theory says that there is an implied agreement between the state and the individual:

- The state provides security and services.

- In return, citizens follow the state’s laws.

- Socrates says he lived in Athens for 70 years, enjoyed its benefits, and chose to stay.

- Therefore, even if the court’s judgment is unjust, he feels obligated to obey the law, because he has already accepted the social contract by living there.

- Later philosophers like Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau developed this into a major political theory.

2. Natural Law Theory

- Civil laws are laws created by the state, but above them exists a universal moral law, known as Natural Law.

- Natural Law can be understood through reason and experience, and is universal, applying to all humans.

- Socrates compares his trial judgment with natural moral law and concludes that the state’s decision was unjust.

- This shows the difference:

- Civil Law: What the state declares.

- Natural Law: What is actually just and morally right.

Summary

Socrates’ thought contains the early foundation of both Social Contract Theory and Natural Law Theory. He believed citizens owe loyalty to the state because they benefit from it, but also believed there exists a higher moral law above state law, which can judge whether the state’s actions are just.

Was Socrates a Sophist?

- Some people think Socrates was a sophist, especially because the playwright Aristophanes portrayed him like one in his comedy The Clouds.

- This play was shown shortly before Socrates’ trial, so many citizens misunderstood him as a sophist.

- However, this idea is incorrect. Socrates and the Sophists had a few similarities, but their core purposes were completely different.

Key Differences Between Socrates and the Sophists

- Different meaning of human excellence (Arete):

- Sophists: Excellence means being successful in society—gaining power, wealth, and status.

- Socrates: Excellence means living a virtuous and moral life, improving the soul.

- Teaching and Money:

- Sophists: They were professional teachers who charged fees for education.

- Socrates: He never charged money and said he had nothing to teach – only to help others discover what they already know.

- Purpose of communication skills:

- Both were skilled speakers, but:

- Sophists: Used communication to win arguments and gain influence (rhetoric).

- Socrates: Used questioning to seek truth and achieve deeper understanding (dialectic).

- View of Knowledge and Truth:

- Sophists: Relativists — believed that truth does not exist, only opinions exist.

(“What is true for you may not be true for me.”) - Socrates: Believed truth does exist and we can discover it through reason and examination.

- Sophists: Relativists — believed that truth does not exist, only opinions exist.

Summary

Although Socrates and the Sophists both discussed human excellence and communication, their goals were opposite. Sophists sought success and persuasion, while Socrates sought truth and virtue. Therefore, Socrates was not a Sophist. He stood for the pursuit of truth, not the pursuit of victory.

Key Takeaways and Final Perspective on Socrates

- Socrates’ impact on philosophy is unique. His influence comes not from written books or formal theories, but from the way he lived and the strength of his character.

- He embodied the true meaning of philosophy — love of wisdom. His commitment to truth was so strong that he accepted death rather than compromise his principles.

- The phrase “Know Yourself” (written at the Temple of Delphi) became the central motto of his life and teaching.

- While earlier Greek thinkers focused on metaphysical questions about the universe, Socrates shifted attention to human life, character, and how to live well.

- Socrates taught that every belief, idea, value, and opinion must remain open to question.

No answer should become final or rigid — it must be reexamined again and again. - In Socrates’ view, questioning is more important than having answers.

The habit of critical reflection is what develops wisdom. - Today, technology gives us quick answers for everything — search engines, calculators, AI systems — and because of this, we have become mentally passive.

- Socrates reminds us that questions are not a burden, they are an opportunity.

Every question is a doorway to deeper understanding. - The teacher we need today is not one who gives answers, but one who asks transformative questions — a modern form of Socratic dialogue.

- The idea of a “Socratic AI Engine” is powerful:

an AI that questions us, challenges our assumptions, and helps us examine our own thinking, rather than simply giving instant answers.

Summary

Socrates’ greatest lesson is that true wisdom comes from continuous questioning and self-examination. His life itself was the message: to care for the soul, seek virtue, and live by truth without compromise. In a world that rewards quick answers, Socrates teaches us to slow down, think deeply, and examine life itself.

Art and Understanding in Socratic Learning

- Some ideas are difficult to understand through words alone, but we can understand them more deeply through art.

- The painting referenced here is meant to help us feel and visualize Socratic wisdom, not just think about it intellectually.

- After the painting, the suggested reading is Plato’s “Symposium and Other Dialogues”.

- These dialogues contain conversations involving Socrates, where his methods, values, and personality become clear through discussion, not explanation.

- Reading these dialogues allows students to experience Socratic questioning directly, rather than just learning about it from summaries.

Summary

This section encourages using art and primary texts to understand Socrates more deeply. The painting offers a visual interpretation, while Plato’s Symposium and Other Dialogues lets us directly observe Socrates’ conversations and philosophical approach.

Recommended Dialogues for Further Study

- At the end of this discussion, the speaker gives two tasks to deepen understanding of Socrates.

- First Task:

Study six major dialogues of Plato which contain Socrates’ discussions:- Euthyphro

- Crito

- Apology

- Meno

- Phaedo (especially important)

- Symposium (often included in the same collection)

- These dialogues help you experience Socratic questioning directly, rather than only reading summaries.

- Second Task:

After reading Phaedo, revisit and study the painting discussed earlier.

Phaedo describes Socrates’ final moments, and the painting will become much more meaningful once the dialogue is understood.

Summary

You are encouraged to read six key dialogues on Socrates and then return to study the related painting, especially after reading Phaedo. These steps will help you connect philosophical ideas with emotional and visual understanding. Thank you for learning along this journey.

Image Credits

“The Thinker” by Auguste Rodin. Photograph by Kaisching, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:

Le_Penseur_by_Rodin_(Kunsthalle_Bielefeld)_2014-04-10.JPG

Leave a Reply