A concise, exam-ready overview of Ancient Atomism, tracing ideas from Leucippus and Democritus to Epicurus and Lucretius. Covers core doctrines — atoms and void, the clinamen (swerve), theories of perception and mind, and ethical implications — with clear dates and student-friendly explanations for quick revision.

Table of Contents

Origins and Key Thinkers of Atomism

- Atomism seeks the answer to Thales’ question about the ultimate reality or first principle of the world.

- The philosophical journey moves from monism and pluralism to its final stage — atomism.

- Four main philosophers are studied under atomism: Leucippus, Democritus, Epicurus, and Lucretius.

- Leucippus is considered the founder of atomism. He lived around 480–420 BC and may have been Zeno’s student. Very little direct information about him survives.

- Democritus, a student of Leucippus, lived around 460–370 BC. He expanded and systematized Leucippus’ ideas; thus, both are often mentioned together as Leucippus and Democritus.

- Epicurus (341–271 BC) revived and developed atomism much later, creating his own school known as Epicureanism, deeply rooted in atomistic thought.

- Lucretius (99–55 BC), though living nearly 200 years after Epicurus, considered him his teacher and expressed his ideas poetically in “On the Nature of Things.”

- Leucippus’s books “The Great World System” and “On Mind” are lost; Democritus wrote over 50 works, with only fragments remaining.

- Many of Epicurus’s writings survive, and Lucretius’s text is almost complete, giving modern scholars valuable insight into atomistic philosophy.

Summary

This section introduces the main philosophers of atomism — Leucippus, Democritus, Epicurus, and Lucretius. It traces how the concept of atoms as the basic reality evolved through their writings, marking a key development in ancient Greek thought.

Basic Concepts of Atomism

- According to Atomism, only two things are real — atoms and empty space (void).

- Atoms are the smallest, indivisible parts of matter — the term comes from Greek atomos, meaning “uncuttable.”

- Atoms are eternal — they are never created or destroyed and exist in infinite numbers.

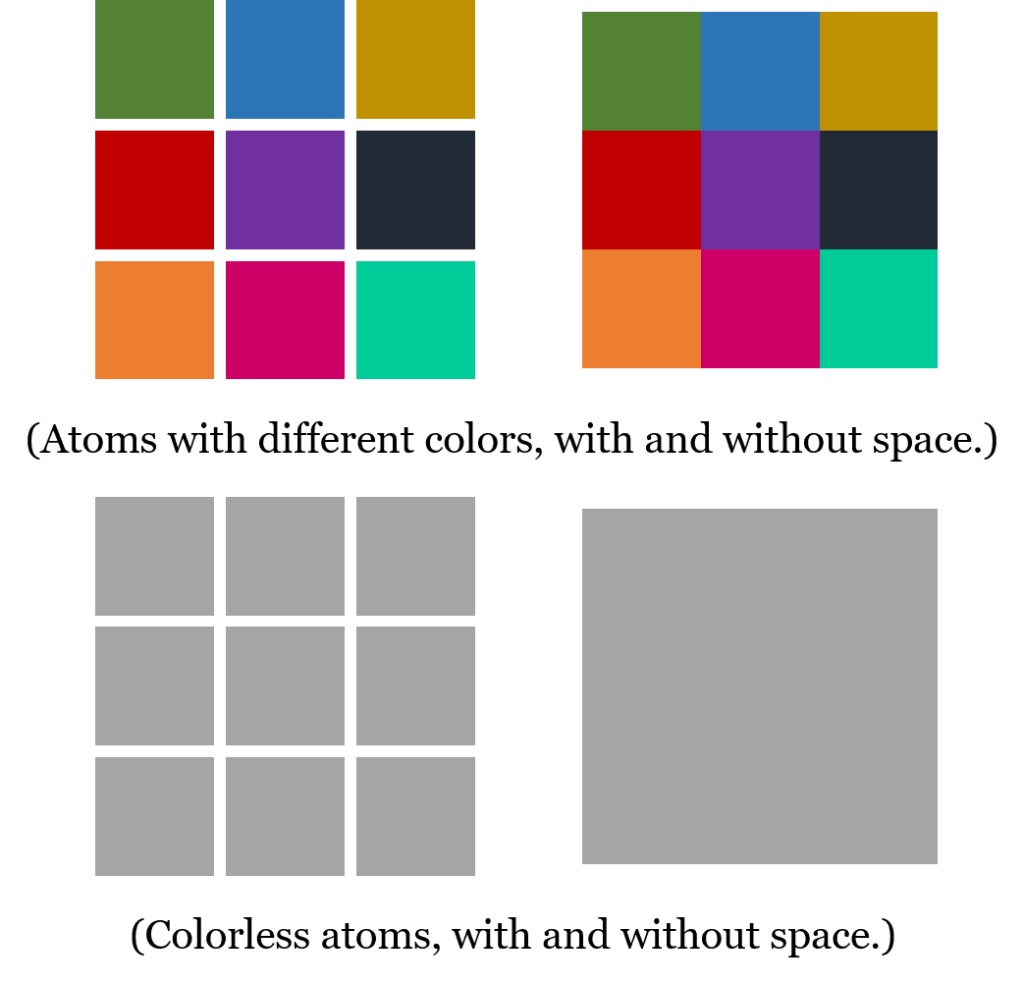

- Atoms differ quantitatively (in measurable ways) such as size and shape, but they are qualitatively neutral — they have no color, taste, smell, or temperature.

- The void refers to empty space where no atoms exist; it allows atoms to move and combine.

- All visible objects — from earth, water, and fire to humans and animals — are combinations of atoms.

- Even the soul (ātman) is considered a very fine form of atom.

- Democritus taught that the world has no divine ordering principle — no mind (nous) or god governs it.

- Every change in the world is due to mechanical motion and cause-and-effect relationships among atoms.

- All variations in objects and phenomena arise from the combination and separation of atoms moving in the void.

Summary

Atomism teaches that reality consists only of atoms and void. Atoms are eternal, innumerable, and indivisible, differing only in size and shape, not in qualities. All changes and forms in the universe come from their movements and rearrangements, without any divine control.

Solving Previous Problems

- Three main issues before Atomism were:

- Qualitative diversity

- Infinite divisibility

- Motion/void.

- Earlier thinkers tried single elements, four roots, or infinite seeds to explain variety.

- Atomists answered these three problems by introducing atoms and void and by shifting from qualities to quantitative explanation.

Summary

Before Atomism philosophers faced three deep puzzles about how things differ, how small things can be divided, and how motion is possible. Atomism proposes atoms and void as the solution framework.

Qualitative Diversity Problem Solved

- Problem: the world shows many qualities (hot, cold, wet, dry, colour, smell, taste). Early theories made the primary stuff possess these qualities.

- Attempts: single-element views, Anaximander’s mixed source, Empedocles’ four roots, and Anaxagoras’ infinite seeds all tried to explain diversity.

- Why they failed: four roots could not generate all particular qualities; infinite seeds remove simplification by giving each object its own unique seed.

- Atomist reply (Leucippus/Democritus): reality is built from atoms that have no sensory qualities.

- Atoms differ only quantitatively in shape, size, arrangement, and position; these differences produce the many observable qualities.

- Example idea: the same atoms arranged differently yield different appearances; colour or taste arise from how atoms strike our senses, not from atoms having those qualities.

Summary

Atomism explains qualitative diversity by denying qualities at the atomic level and deriving colours, tastes, and other qualities from quantitative differences — shape, size, arrangement, and position of atoms.

Infinite Divisibility Problem Solved

- Problem: Anaxagoras (influenced by Parmenides) argued matter is divisible without end; Zeno used this to attack plurality.

- Zeno’s paradox: infinite parts either give infinite total size or no size at all, so plurality seems impossible.

- Leucippus’ counter: if matter were infinitely divisible, objects would either vanish or become infinite — but real objects have definite size.

- Solution: there must be a last indivisible part — the atom — where division stops.

- Atoms are like a Parmenidean one: uncreated, indestructible, eternal, indivisible, and lacking internal void.

- Result: plurality is preserved because reality consists of many atoms, not one continuous substance.

Summary

Atomism ends the regress of endless division by positing indivisible atoms. This preserves definite sizes for objects and secures plurality against Zeno’s paradox.

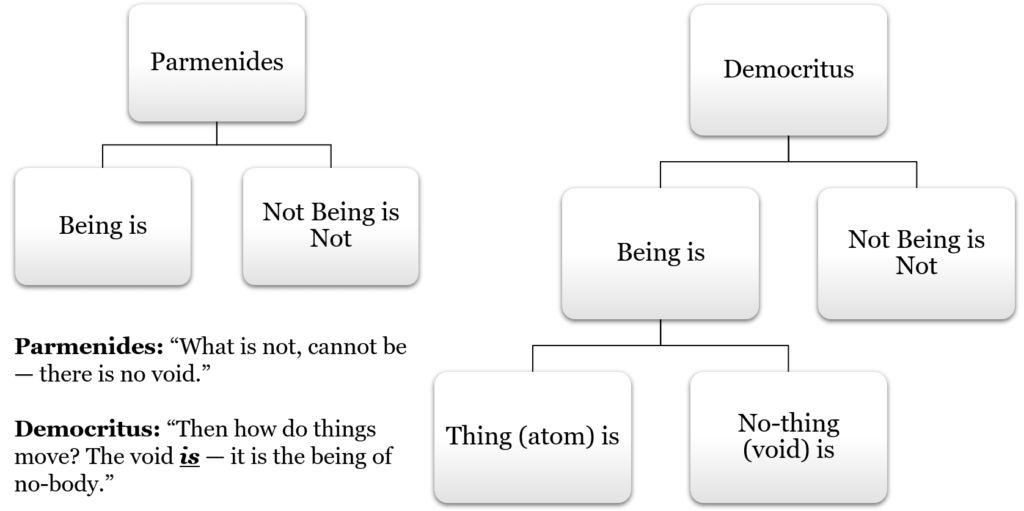

Motion and Void Problem Solved

- Problem: if objects form by atomic rearrangement, motion must be possible. But some thinkers (Empedocles, Anaxagoras) denied empty space (plenum), claiming motion occurs without void.

- Empedocles’ experiment (water & tube) suggested parts of a full medium can move without empty space.

- Atomist objection 1: solid atoms cannot mix into one another; if every body is a Plenum, distinct atoms could not move or remain separate.

- Atomist objection 2: quality-less atoms need space to be counted as many; identical, adjoining, quality-less bits would become a single body without void between them.

- Therefore void (the no-thing) must be real — a kind of being without body that allows atoms to move, collide, and remain distinct.

- Democritus calls this void a being where bodies do not exist; this raises a metaphysical question: can a being exist without a body?

Summary

Atomism restores motion by positing void as a real entity. Void gives atoms room to move and remain distinct, enabling collisions and the formation of objects.

Lucretius’ Version of Atomistic Physics

- Lucretius, a Roman poet, explained Atomism clearly in his work “On the Nature of Things.”

- His account helps us understand Atomism better since Leucippus’s works are lost and only fragments of Democritus’s writings survive.

1. Nothing Is Created

- Lucretius’ first principle: Nothing comes from nothing.

- Every object has a source that already exists — oil comes from seeds, ghee from milk, etc.

- If creation could happen without a source, anything could come from anything, like a magician pulling a rabbit from a hat.

- Thus, nature follows fixed causes and processes, not divine miracles.

- Gods exist but have no role in creating or controlling the world; they live far away and remain indifferent.

- Nature works regularly according to laws and causes, freeing humans from fear of divine punishment.

2. Nothing Is Destroyed

- Like Parmenides, Lucretius said nothing can be destroyed.

- He used observation, not just logic, to prove this:

- If destruction were real, everything would have vanished over infinite time.

- Since the world still exists, reality must be eternal.

- Matter only changes form, never disappears.

3. There Is Empty Space

- Empty space (void) exists between all things; otherwise, motion would be impossible.

- Lucretius used everyday examples:

- Sound passes through walls, proving tiny gaps or spaces exist.

- Two objects of equal size (like a cotton ball and iron ball) differ in weight because one has more empty space inside.

4. Space Is Infinite

- Void is infinite — there is no ultimate boundary or edge.

- If someone reached the “end” of space and threw a ball:

- If it moved forward, space continued beyond.

- If it bounced back, it hit something that also exists in space.

- Therefore, space has no end; it stretches infinitely in all directions.

5. The Nature of Atoms

- Since space is infinite, atoms must also be infinite; otherwise, limited atoms would get lost in limitless space and could never form a world.

- The world’s existence proves atoms collide and combine, forming visible matter.

- Atoms are extremely small and invisible, just as air is unseen but real.

- Matter is not infinitely divisible — division ends at the smallest unit, the atom.

- Lucretius argued that if everything were infinitely divisible, no difference would exist between a desert and a grain of sand — both would have infinite parts.

- Hence, atoms are indivisible realities forming all things.

6. Knowledge of Atoms

- Atoms cannot be directly perceived by the senses; they are known through reason and inference.

- Lucretius often mixed up sense-based knowledge with rational inference, leading to confusion about atomic motion.

- In truth, atoms are a rational concept, not an object of direct experience.

Summary

Lucretius presented a detailed, observation-based version of Atomism, asserting that nothing is created or destroyed, empty and infinite space exists, and atoms are eternal and countless. His reasoning removed divine control from nature, showing that all change and order arise from natural atomic motion governed by reason and law, not by gods.

The Motion of Atoms in Epicurean Atomism

- All Atomist philosophers agreed that infinite atoms move in infinite space, constantly colliding and separating, creating the world we see.

- The terms “jostling” (pushing or crowding motion) and “colliding” (striking together) describe how atoms interact.

- However, they disagreed on the cause of atomic motion — why atoms move at all.

1. Democritus: Motion Is Eternal and Natural

- Democritus believed that motion has always existed.

- For him, atoms have always been in motion by their very nature — no external cause is needed.

- Motion is eternal, not started or stopped by anything.

2. Epicurus: Searching for a Cause

- Epicurus was not satisfied with this explanation; he wanted a rational cause for motion.

- Using sense observation, he noted that all things are either at rest or in motion.

- People often assume rest is natural, and motion needs a cause, like a stone moving only when pushed.

- But Epicurus asked: could there be motion that is natural, like rest, not caused by anything?

3. Free Fall as Natural Motion

- Epicurus observed that objects fall downward naturally — this is called free fall.

- When a stone is thrown up, it returns down without any external agent; thus, falling is a natural, eternal motion.

- In infinite space, this free fall has no beginning or end — atoms have been falling forever.

4. The Problem of Straight-Line Fall

- If all atoms fall straight downward forever, they would never collide — no interactions, no world formation.

- For collisions to occur, atoms must somehow deviate from their straight paths.

5. The “Swerve” (Vichlan or Bhatkāv)

- To solve this, Epicurus proposed the idea of a swerve — a tiny, random deviation in the path of some atoms.

- This minute, unobservable shift allows atoms to collide and form complex structures.

- However, this idea introduces a spontaneous, uncaused event, which contradicts Atomism’s mechanical order.

6. Lucretius’ Reaction

- Lucretius, a follower of Epicurus, included the swerve theory in “On the Nature of Things” but felt embarrassed by it.

- He admitted the swerve cannot be observed, yet still used it to justify collisions and free will.

- The problem remains: if Atomism denies divine intervention and insists on cause-and-effect, how can an uncaused swerve exist?

Summary

Democritus viewed motion as eternal and natural, while Epicurus tried to find a cause for it, proposing the idea of a natural free fall. To explain collisions, he introduced the “swerve” — a random, uncaused deviation in atomic paths. Though Lucretius accepted this view, it created a deep philosophical tension within Atomism, as it broke the rule of universal causality that Atomists themselves had established.

The Sensory World in Atomism

- When atoms collide and combine (due to the swerve), they form different kinds of bodies — some tightly packed like iron or stone, and others loosely arranged like air or light.

- This explains the physical diversity of the world, but raises a key question:

If atoms have no qualities, how do objects get qualities like color, taste, or smell?

Epicurus’ View: Properties and Accidents

- Epicurus tried to solve this by distinguishing between properties (essential attributes) and accidents (non-essential, temporary attributes).

- Properties are necessary for a thing’s identity — e.g., roundness is a property of a circle.

- Accidents can change without changing the object — e.g., a car’s color.

- According to Epicurus:

- A collection of atoms always has some color (a property).

- But which color (red, blue, yellow) is accidental — it can change with atomic arrangement.

- Thus, qualities are temporary and external, not part of the atoms themselves.

- This explanation creates an ontological problem — if only atoms and void are real, then where and how do qualities like color exist?

They are neither atoms, nor void, nor combinations — so their existence becomes unclear.

Democritus’ View: Sensation Is Interaction

- Democritus gave a radically different answer: qualities are not real; they are the result of interaction between atomic bodies.

- Example: A rose is just a collection of atoms.

- Its atoms collide and bounce, and some tiny atoms travel toward our sense organs.

- Our eyes or nose (also made of atoms) are struck, causing motion in our sensory atoms.

- This motion travels through nerves, creating a sensation — the experience of “seeing” or “smelling” a rose.

- Hence, color, fragrance, or taste are not in the object; they are effects of atomic interaction.

- The world we experience is therefore subjective, not identical to objective reality.

Objective vs. Subjective World

- For Epicurus, sensations show objective reality — qualities exist in the objects themselves.

- For Democritus, sensations are subjective experiences, differing from person to person.

- Example: A rose’s fragrance might seem pleasant to one and dull to another.

- Therefore, what we perceive is not the world as it is, but how our atomic structure reacts to it.

- Reality, according to Democritus, consists only of atoms and void; qualities are illusions born from atomic interactions.

Atomism’s Reply to Sophism

- The Sophist philosopher Protagoras said: “Man is the measure of all things,” meaning truth is relative to each person’s perception.

- For him, every experience is valid — cold air for one, warm for another — both are right.

- Epicurus would reject this, saying the object itself has a fixed color or quality, so one perception must be wrong.

- Democritus, however, supports Protagoras’ relativity indirectly — since qualities are subjective, perception differs for everyone.

- Thus, Atomism provides a material explanation for how subjective experiences arise from objective atomic interactions.

Summary

Epicurus and Democritus offered two contrasting views on the sensory world. Epicurus held that qualities exist temporarily in atomic collections, while Democritus argued that qualities are not real, but subjective effects of atomic collisions on our senses. This distinction introduced a deeper insight — the world we experience is not identical to the world that truly exists, which consists only of atoms and void.

Atomism and the Psychology of Mind

- According to Atomism, the human person, mind, and sense organs are all made of atoms.

- The mind is material, a physical organ made of finer and more complex atoms than those of ordinary objects.

- The difference between a machine and a mind lies in complexity, not in kind — both are atomic structures, but the mind’s atoms are more subtle and dynamic.

1. The Nature of Thought

- If the mind is made of atoms, then even thinking must arise from atomic motion.

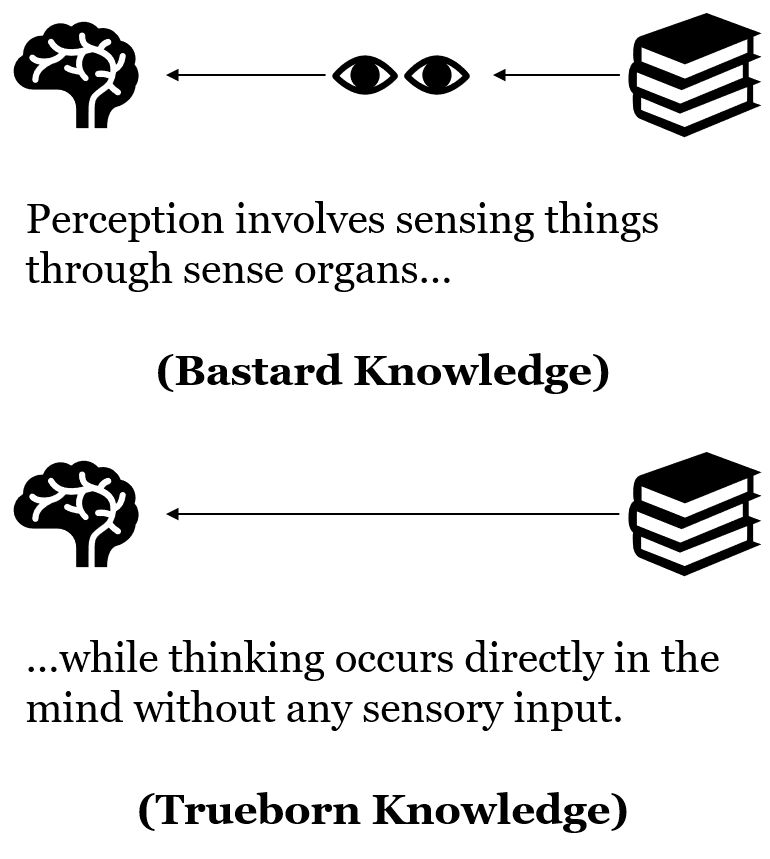

- For Atomists, thinking is similar to perception, but without the use of sense organs.

- In perception, external objects send streams of atoms that strike our sense organs and then move into the mind.

- In thinking, atoms of the desired object reach the mind directly, without sensory mediation.

- Hence, to see something means atoms reach the mind through senses, while to think means atoms reach the mind directly.

- Democritus divided knowledge into two kinds:

- Trueborn (objective) knowledge – direct, rational awareness of atoms and void.

- Bastard (subjective) knowledge – sensory knowledge based on appearance, which is deceptive and illusory.

- Thus, sense-based knowledge (color, sound, taste, etc.) is unreliable, while reason-based understanding of atoms and void is real knowledge.

- This view makes thinking and reasoning a mechanical process — motions of mental atoms interacting like colliding balls.

- However, logical reasoning (like combining premises to reach a conclusion) cannot be fully explained by mechanical motion, since logical relations are conceptual, not physical.

2. The Problem of Free Will

- If thought and decision-making are also just atomic motions, then human freedom becomes an illusion.

- Every decision we make — for example, whether to go for a walk or stay in bed — is simply the result of atomic interactions in the mind.

- These atomic movements follow a chain of cause and effect:

- Each movement is determined by a previous movement, which was also caused by an earlier one.

- This sequence extends infinitely backward in time.

- Therefore, every action or decision was already determined by the positions and motions of atoms long before we were born.

- This idea leads to necessity (determinism) — everything that happens must happen exactly as it does.

- What we call free choice is merely a feeling, not a fact; in truth, we could not have chosen otherwise.

- Lucretius tried to solve this by referring to Epicurus’ “swerve”, a tiny, random deviation in atomic paths, as the source of freedom.

- But this solution creates further contradictions, since an uncaused motion (the swerve) breaks Atomism’s rule of universal causality.

Summary

In Atomism, the mind is physical, made of atoms, and thoughts are forms of atomic motion. Knowledge through senses is unreliable, while reason reveals the true reality — atoms and void. However, this mechanical explanation of mind leads to the problem of free will: if all mental motions are determined by atomic causes, then freedom and choice are mere illusions, fixed long before by the eternal motion of atoms.

Ethics in Atomism: Living in a Material World

- The key ethical question for Atomists is: “How should we live?”

- But in a universe made only of atoms and void, where free will doesn’t exist and all actions are pre-determined, the idea of ethics becomes complex.

- Democritus did not deeply link his ethical ideas with his atomic theory; his ethics is more practical than theoretical.

1. Democritus’ Practical Moral Teachings

- His ethical sayings focus on self-control, moderation, and character:

- “It is hard to fight desire, but to overcome it is the mark of a rational man.”

- “The needy animal knows how much it needs, but the needy man does not.”

- “In cattle, excellence is in strength of body, but in men, it lies in strength of character.”

- These thoughts emphasize self-discipline, contentment, and inner strength, rather than dependence on external pleasure or wealth.

2. Ethical Idea Linked to Atomic Theory

- One statement by Democritus connects ethics with atomic movement:

- “Equanimity comes through proportionate pleasure and moderation in life. Excess and defect disturb the soul.”

- Here, the word “moved” is central — since all experiences are movements of atoms within us.

- A good life is one where the motion of atoms (our sensations and feelings) is gentle and balanced, not violent or chaotic.

- Too little motion means dullness, too much motion means suffering — thus, moderation creates pleasure and stability.

- Ethical balance, therefore, reflects a physical balance in atomic motion within the body and mind.

3. The Principle of Moderation

- Moderation (sōphrosynē) is the path to tranquility (equanimity).

- When atomic movements are stable and calm, the mind (soul) experiences peace and happiness.

- When movements are excessive or disordered, the soul experiences pain and anxiety.

- Hence, virtue and happiness depend on maintaining moderate atomic motion — neither still nor turbulent.

4. Ethical View in Summary

- Democritus’ ethics is practical and materialistic, grounded in the balance of physical motion within us.

- A happy life means balanced sensations, moderate desires, and inner calm.

- This ethical idea subtly connects moral harmony with atomic equilibrium, showing that even in a world without gods or free will, peace and goodness come from measured living.

Summary

In Democritus’ view, ethics is about living with moderation and achieving equanimity through balanced atomic movement. Though his ethical ideas don’t directly depend on his physics, they align with it: when the motions of atoms are gentle and orderly, the mind experiences pleasure and peace. Thus, the moral life is one of self-control, harmony, and moderation — a calm rhythm within the eternal dance of atoms.

Evaluation of Atomism: Its Strengths and Limitations

- Atomism presents a universe made only of atoms and void, where everything happens through cause and effect, with no divine control or intervention.

- Even gods, according to Epicurus, are merely complex atomic collections, far removed from human affairs.

- The theory rejects faith and authority, relying instead on reason, logic, and evidence — a revolutionary step toward scientific thinking.

1. The Historical Achievement of Atomism

- Atomism solved many earlier philosophical problems about change, plurality, and reality.

- Thales had proposed that everything came from one basic material (water). Later thinkers like Anaximander, Heraclitus, Empedocles, and Anaxagoras refined this idea but left logical gaps.

- Leucippus and Democritus fixed these issues by proposing indivisible atoms and void, offering a consistent explanation of change and diversity.

- They redefined change not as transformation of substance (like water turning into ice), but as change of place — the rearrangement of atoms.

- This shifted philosophy from mythical and sensory explanations to rational and mechanical understanding of nature.

2. Philosophical and Conceptual Advances

- Atomism transformed the concept of matter (stuff) — no longer based on sensory qualities like color or taste, but on invisible, quality-less particles.

- It introduced a scientific worldview, anticipating later mechanistic physics and materialism.

- The idea that all change can be explained by motion and arrangement of atoms laid the foundation for modern science.

3. Weaknesses and Ethical Limitations

- Atomism struggles with ethics and morality.

- If all actions are fixed by atomic motion and free will doesn’t exist, moral responsibility loses meaning.

- Questions like “Why be honest?” or “Why act rightly?” cannot be answered within a deterministic system.

- It also offers no spiritual or existential meaning — life becomes a mechanical process rather than a purposeful journey.

- Religion, which gives people hope and meaning in suffering, finds no space in Atomism.

- This is why, during the Middle Ages, Atomism was largely ignored, while Plato and Aristotle were emphasized for their harmony with religious and moral values.

4. Continuing Relevance of Atomism

- Despite its rejection in the medieval period, Atomism regained importance in the 17th century with the rise of modern science.

- The questions it raised — about matter, motion, mind, and free will — resurfaced in the works of John Dalton, J.J. Thomson, Niels Bohr, and Heisenberg.

- Thus, Atomism became the philosophical ancestor of modern atomic theory and scientific materialism.

Summary

Atomism marked a turning point in human thought — replacing myth and faith with reason, evidence, and causality. It offered a clear, logical model of nature but struggled to explain ethics, purpose, and meaning. Though overshadowed in religious times, its rational spirit later inspired modern physics and philosophy, shaping how we understand reality, matter, and change even today.

Leave a Reply