A clear, student-friendly guide to Plato’s Divided Line, Sun analogy, Cave allegory, Forms, and the Form of the Good. Easy notes for exams, UPSC, and philosophy study.

Table of Contents

Plato’s Two Worlds and Types of Forms

- Plato explains that true knowledge is fixed and unchanging, so it cannot come from the changing physical world.

- This leads him to argue for two worlds: the world of senses (physical/visible world) and the world of forms (intelligible world).

- The world of forms can be known only through reasoning, not through sense experience.

- In this intelligible world, Plato says there are geometrical forms, such as the perfect circle, triangle, or square.

- There are also ethical forms, like Justice, Good, Bad, Right, and Wrong. These are harder to understand but still exist as real forms.

- Plato notes that Mathematics and Science also depend on forms. Scientists study many particular things to understand the universal form behind them.

- For Plato, Science means universal and necessary truths, which stay the same everywhere and cannot change.

- A scientist observes the sensory world to understand the unchanging forms that lie behind it.

Summary

Plato argues that real knowledge comes from the unchanging world of forms, not the shifting world of senses. These forms include geometrical, ethical, and scientific universals. Science and reasoning help us move from particular things to these universal truths.

Relation Between Forms and Senses

- We can understand the relation between the world of forms and the world of senses with the help of the example of a hand and its shadow.

- The hand is presented as a higher reality, while the shadow is a less real copy.

- The shadow depends on the hand for its existence; without the hand the shadow cannot appear.

- By observing different variations of the shadow, we can form a mental idea of the unseen hand.

- The shadow acts only as a medium; the true source of understanding is the hand itself.

- The hand gives the shadow consistency and intelligibility, making the shadow understandable.

- Both hand and shadow exist in the physical world, showing how cause and effect work within the sensible realm.

- Plato says a similar pattern holds: the world of forms (like the hand) explains and grounds the world of senses (like the shadow).

Summary

The hand–shadow example shows how a higher, unseen reality gives existence and meaning to a lower, visible reality. Studying the visible things helps us form ideas of the unchanging forms that underlie them.

Plato’s Three Main Analogies

- Plato uses three main analogies to explain his philosophy.

- These analogies are:

- The Divided Line

- The Sun

- The Allegory of the Cave

- All three appear together in his book Republic.

- They are presented in a dialogue between Socrates and Glaucon, who is Plato’s brother.

Summary

Plato explains his ideas in the Republic through three key analogies: the Divided Line, the Sun, and the Cave. These help Socrates guide Glaucon toward understanding the theory of forms.

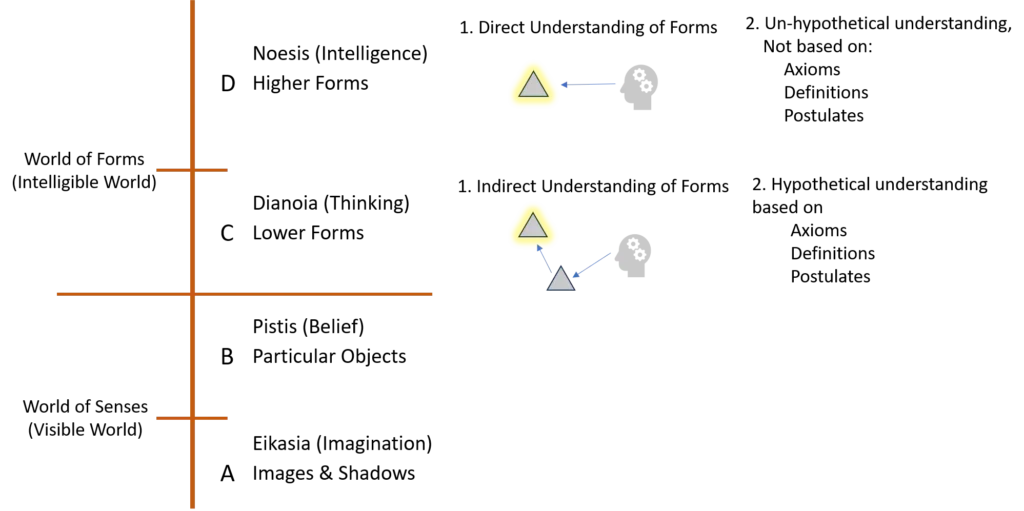

Plato’s Divided Line Analogy

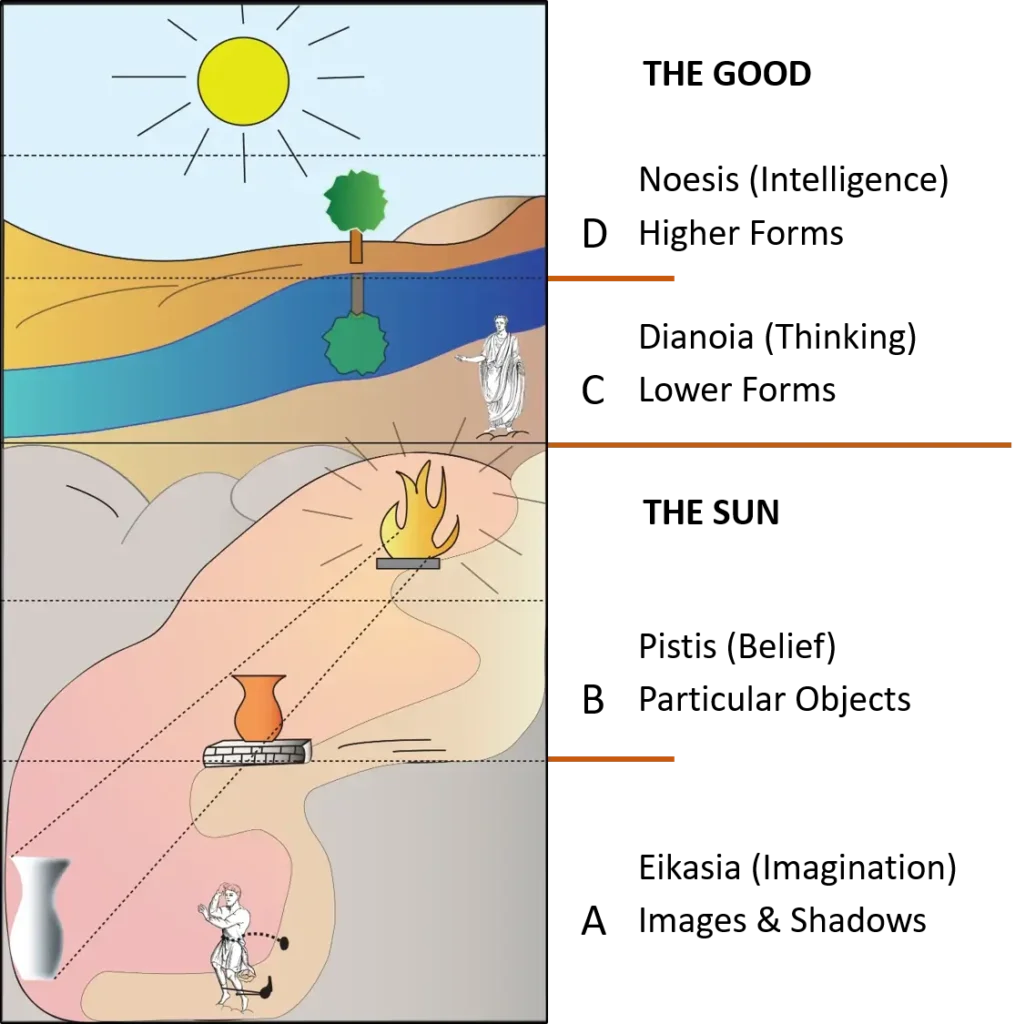

- Socrates asks us to draw a line and divide it into two unequal parts: the visible world (world of senses) and the intelligible world (world of forms).

- Each of these two parts is then divided again in the same proportion, creating four segments: A, B, C, and D.

- Section A contains images such as shadows and reflections.

- Section B contains the actual physical things whose images appear in Section A (objects, humans, animals).

- Section C contains mathematical and scientific concepts, also called lower forms.

- Section D contains the higher forms, which represent the highest level of reality and knowledge.

Summary

The Divided Line analogy divides reality into four levels: images, physical objects, lower forms, and higher forms. This structure helps explain how our understanding shifts from sensory impressions to the highest forms of truth.

Divided Line: Section A & B (Imagination & Belief)

- The Divided Line contains four stages, which also represent four levels of cognition.

- Cognition means the mental process through which we see, understand, or remember anything.

- Section A shows the lowest level of cognition, where a person accepts shadows as real. Plato calls this eikasia (imagination).

- At this stage, the mind is dull and simply believes whatever is shown or told.

- Section B contains all visible objects like humans, animals, plants, tables, chairs, or laptops.

- Cognition of these objects is called pistis (belief), which depends completely on sense experience.

- Belief can be true or false because there is no reasoning or justification involved yet.

- Plato says knowledge is justified true belief (JTB), so this level is not knowledge—only belief without justification.

Summary

Sections A and B of the Divided Line show the lower levels of cognition. Section A is imagination (eikasia), where shadows are taken as real, and Section B is belief (pistis), based only on sense experience. These levels lack reasoning and justification, so they do not count as true knowledge.

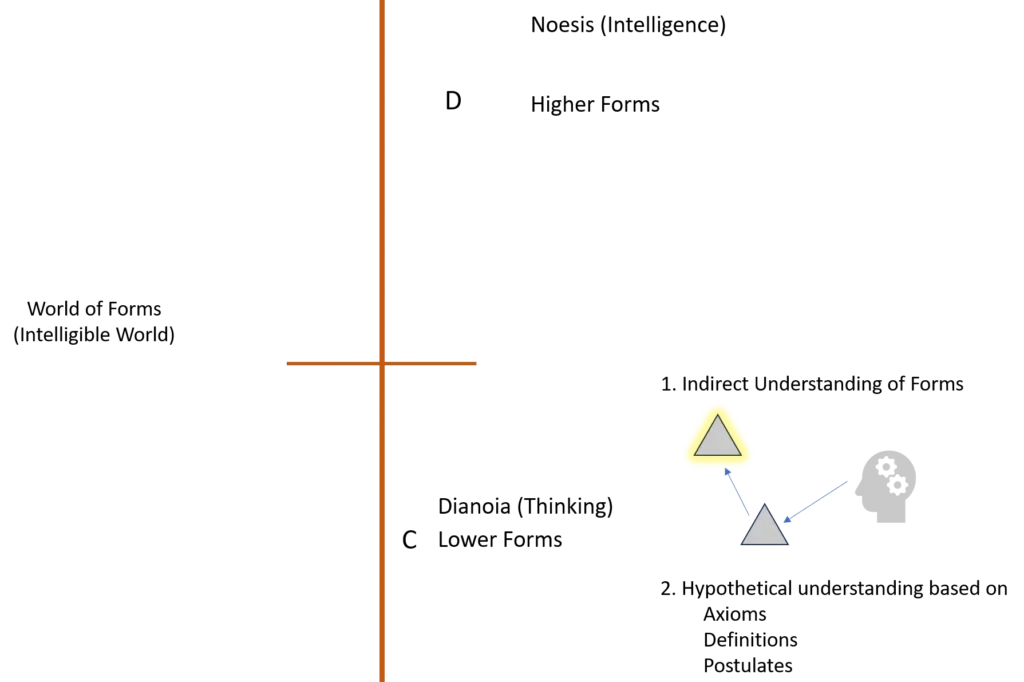

Divided Line: Section C (Mathematical and Scientific Concepts)

- Section C focuses on mathematical and scientific concepts, where a person understands forms in an indirect and incomplete way.

- At this level, we use visible diagrams or models to think about the forms behind them.

- A mathematician draws a triangle and studies the diagram to understand the form of triangularity, which exists on its own.

- The diagram is only a shadow or weak copy of the real form, but it helps the mind reach the form indirectly.

- The mathematician knows he is not studying the drawn shape itself; he is using it to understand the unchanging form behind it.

- Here, we use both senses and reasoning. Senses provide the diagram, and reasoning leads us toward the form.

- At this stage, we start thinking about something changeless and eternal, even though we do not directly access it.

- The same method works in science. A biologist studies many particular bodies to understand the universal body, the form that applies to all humans.

- Scientific study combines observation and reasoning to move from changing physical things toward their universal properties.

Summary

Section C shows how we reach forms indirectly through diagrams and scientific observations. By using both senses and reasoning, we gain a partial but meaningful understanding of the unchanging forms that lie behind changing objects.

Axioms Behind Mathematical and Scientific Thinking

- Plato says that mathematical and scientific knowledge is built on axioms.

- Axioms are statements we do not question; they are self-evident and need no proof.

- From these axioms, we deduce conclusions, step by step.

- Euclid’s geometry is an example: it begins with simple axioms such as:

- A straight line can be drawn between two points.

- A straight line can be extended infinitely.

- A circle can be drawn using a center and a radius.

- These axioms are accepted as already true, and new results in geometry are developed from them.

- This shows how mathematical reasoning depends on starting assumptions that guide all further understanding.

Summary

Plato explains that math and science rely on axioms—self-evident statements that we do not question. Using these axioms, thinkers like Euclid deduce new conclusions, showing how reasoning builds knowledge in a structured way.

How We Get New Ideas from Axioms

- Imagine we start with five axioms: A, B, C, D, and E.

- These axioms are accepted as already true, so we do not question them.

- Using these axioms, we use logic to find new results.

- Example: if A, D, and E are true, then F must also be true.

- Now we have six truths: A, B, C, D, E, and F.

- Next: if A, B, and F are true, then G must be true.

- Then: if F and G are true, then H must be true.

- So we keep moving step by step: from what we already know → to what must also be true.

- This is how new conclusions are built from a few basic starting points.

Summary

We begin with a small set of axioms. Using logic, we keep adding new results like F, G, and H. Each new idea comes from what was already accepted as true.

Why Section C Is Still Limited (Dianoia)

- All sciences begin with some axioms, which are statements we accept as true without proof.

- In arithmetic, we use Peano axioms to define natural numbers and build all basic and complex results.

- In physics, we accept axioms like “every effect has a cause,” which is treated as self-evident.

- Even ethics uses axioms, such as assuming that humans have free will, so we can judge actions as good or bad.

- Plato says that every branch of math and science starts with these self-evident premises.

- We then use logic to deduce new conclusions, but those conclusions are true only if the axioms are true.

- Axioms are never proved, so the whole system has no solid foundation.

- If even one axiom turns out to be false, the entire structure of knowledge would fall apart.

- This level of thinking is called dianoia, which means step-by-step or discursive thinking.

- Dianoia is not perfect understanding because:

- We understand forms indirectly using diagrams, images, and particular objects.

- Our knowledge rests on assumptions we never prove.

- So Section C represents thinking that is helpful but still incomplete.

Summary

Section C shows that math and science depend on unproven axioms. We use these axioms to build new ideas, but this thinking (dianoia) gives only indirect and incomplete understanding of forms.

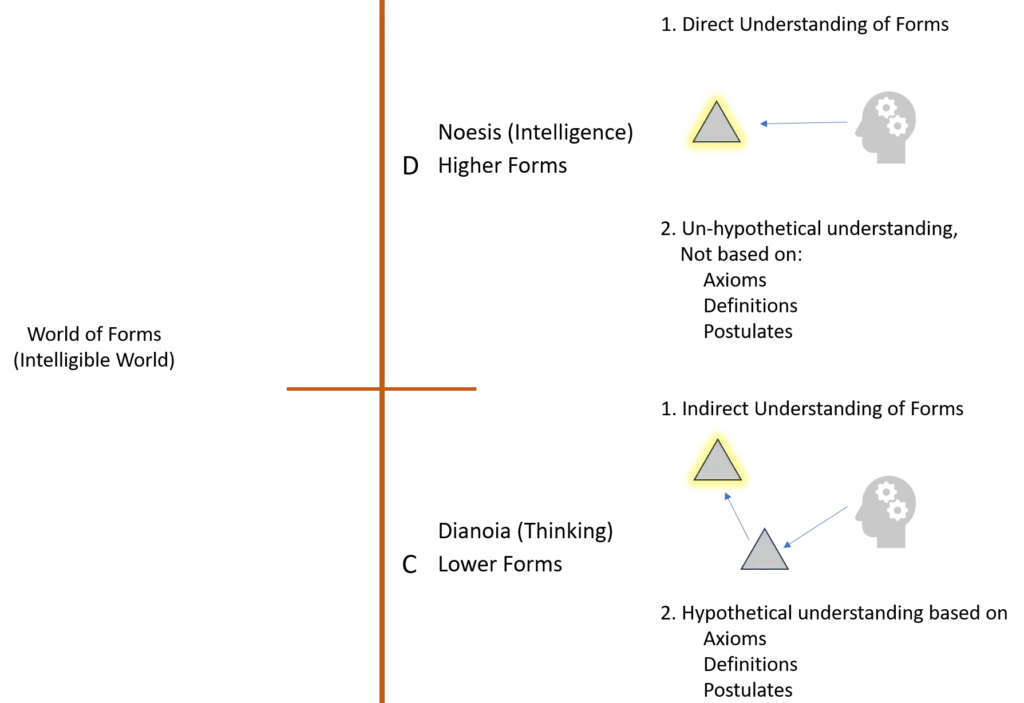

Direct Knowledge of Forms (Section D)

- Section D represents the highest level of cognition.

- At this stage, we come into direct contact with the forms.

- Earlier stages needed diagrams, images, or particular objects to understand forms, but here no medium is used.

- This is a kind of direct intuition—the mind understands the form itself in its pure and perfect state.

- At this level, reasoning also changes direction.

- In the previous stage, reasoning moved forward, starting from axioms and using them to deduce new conclusions.

- But in Section D, reasoning moves backward.

- We now examine the very axioms and assumptions we earlier accepted as self-evident.

- We ask: Where do these axioms come from? What is their foundation?

- By moving backward, we search for the first principle or supreme form that acts as the foundation for all other axioms.

Summary

Section D shows the highest understanding, where the mind directly grasps the forms without using images. Reasoning also turns backward to find the first principle that supports all other assumptions.

Noesis and the Role of Dialectic (Section D)

- Euclid built his geometry on five postulates, and for 2000 years people accepted them as self-evident.

- Later, some mathematicians examined the fifth postulate and showed that it was not fully consistent.

- Plato uses this to explain that axioms we treat as self-evident are still assumptions or hypotheses.

- Any system built on assumptions will also be hypothetical, so we must look behind these assumptions.

- To do this, Plato introduces the method of Dialectic—a question–answer technique that examines assumptions step by step.

- Using dialectic, we move backward from assumptions to their source, searching for the first principle.

- Plato says this method studies forms directly, without any diagrams or images.

- He used this technique at his Academy, although no written record shows exactly how he practiced it.

- This highest cognitive level is called noesis, meaning intelligence or direct intuition.

- At this level, we understand forms in their purest sense, and Plato says only here can cognition truly be called knowledge.

Summary

Section D describes noesis, the highest level of understanding, where forms are grasped directly. Using dialectic, we question our assumptions and trace them back to a first principle, allowing true knowledge rather than hypothetical thinking.

Difference Between Level C and Level D Methods

| Dianoia (Thinking) | Noesis (Intelligence) |

|---|---|

| Mathematics/Other Sciences | Philosophy/Dialectic |

| Use Axioms as Self-Evident | Use Axioms as Assumptions |

| Scientists use Induction | Philosophers examine Induction |

| Use Logic | Also examine Logic (Meta-Logic) |

| Religion – Follows God | Philosophy – Questions God? |

- Level C uses the method of mathematics and sciences, while Level D uses the method of dialectic.

- In mathematical sciences, we begin with axioms, definitions, and postulates that are treated as self-evident starting points.

- From these starting points, knowledge is built step by step through deduction.

- In philosophy, the same axioms are treated as hypotheses, and we examine their foundation instead of accepting them.

- For example, arithmetic uses axioms to build results, but the philosophy of mathematics questions the meaning of number, addition, or geometric ideas.

- Scientists use methods like induction, but in the philosophy of science, these methods themselves are examined and questioned.

- Logic is used in every discipline, but in philosophy we study the logical system itself, not just how to use it.

- A good logician is someone who understands the structure behind logic, not just how to apply it.

- Philosophers see axioms as assumptions, not as unquestioned truths, so they examine every axiom.

- The same happens in philosophy of religion: instead of assuming God exists, we first question the existence of God.

- A second key difference: sciences use particular objects or models to reach universal ideas, but dialectic studies general and abstract concepts directly, without any medium.

- These two differences show how Level C and Level D represent two very different methods of understanding.

Summary

Level C uses the method of mathematics and science, which starts from self-evident axioms and builds conclusions from them. Level D uses dialectic, which questions those assumptions and studies abstract concepts directly. These two methods show the difference between scientific thinking and philosophical thinking.

Understanding the Four Levels with a Horse Example

- We use a horse named Fido to make Plato’s four levels very easy to understand.

- Level 1: Imagination – A person has never seen a horse. They only heard stories about Fido. These stories are like shadows or rough images, not real knowledge.

- Level 2: Belief – A person has seen Fido or other horses, but only with their senses.

- They may notice patterns, like horses with certain body shapes running faster.

- But they do not know why this happens, so their understanding is still limited.

- Level 3: Thinking – A biologist studies many horses carefully and uses logic and scientific reasoning.

- They understand horseness in a deeper, conceptual way by studying anatomy, genetics, and behavior.

- Level 4: Intelligence – A philosopher understands the form of horseness directly, without looking at real horses or diagrams.

- This is the purest knowledge, not based on senses or assumptions—just direct understanding.

Summary

The example of Fido shows four levels of knowing: hearing stories, seeing with senses, scientific reasoning, and finally direct understanding of the form. Each level is deeper than the one before, with the fourth level giving complete knowledge.

Understanding AI Through the Four Levels

- We can also use Artificial Intelligence (AI) as a modern example to understand the Divided Line.

- Level 1: Imagination – A person knows AI only from movies or stories. Their ideas are based on illusions, not reality.

- Level 2: Belief – A person uses AI tools like Grammarly, ChatGPT, or Gemini but does not know how they work.

- This is like driving a car without knowing anything about the engine.

- Level 3: Thinking – Here we study the science behind AI: data processing, machine learning, computer science, mathematics, neuroscience, and game theory.

- We try to understand how AI systems actually function.

- Level 4: Intelligence – At this stage, we study the essence of AI.

- We ask deep questions like: What is intelligence? Can AI truly create intelligence? What does it mean to create intelligence?

- We also explore the problem of consciousness: Is AI conscious? If yes, in what sense?

- At this level, we deal with very abstract and philosophical ideas about mind, awareness, and technology.

- In AI, the fourth level becomes extremely complex because many disciplines—science, philosophy, psychology, and technology—all meet at one point.

Summary

AI can also fit into Plato’s four levels: imagination (AI in movies), belief (using AI), thinking (studying how AI works), and intelligence (studying the deeper nature of intelligence and consciousness). The fourth level becomes the most complex because it raises deep philosophical questions.

The First Principle and the Form of the Good

- Higher levels of knowledge always make the lower levels clearer.

- A person at Level 2 can understand shadows better than someone at Level 1, and someone at Level 3 can understand Level 2 even more clearly.

- This means: the higher you go, the more understandable the lower stages become.

- At the very top, there is a point where everything becomes completely clear.

- As we move upward, the subject matter also becomes more abstract.

- We start with shadows, then go to particular objects, then to general concepts, and then to even higher abstract ideas.

- You can imagine the whole structure like a pyramid:

- Lower levels = more dependent, more crude, more limited knowledge.

- Higher levels = less dependent, more abstract, more refined knowledge.

- Plato says the pyramid’s highest point is a stage where knowledge is unconditioned, independent, and absolute.

- This point needs no medium and no extra explanation—it explains itself.

- This highest point is the first principle, which Plato calls the Form of the Good.

- The Form of the Good is very hard to explain, so Plato uses another analogy to help us understand it.

Summary

Plato believes that higher knowledge makes lower knowledge clearer, and as we rise upward, ideas become more abstract. At the top of this pyramid is the first principle—the Form of the Good—which is unconditioned and absolute. It is the source that makes everything else understandable.

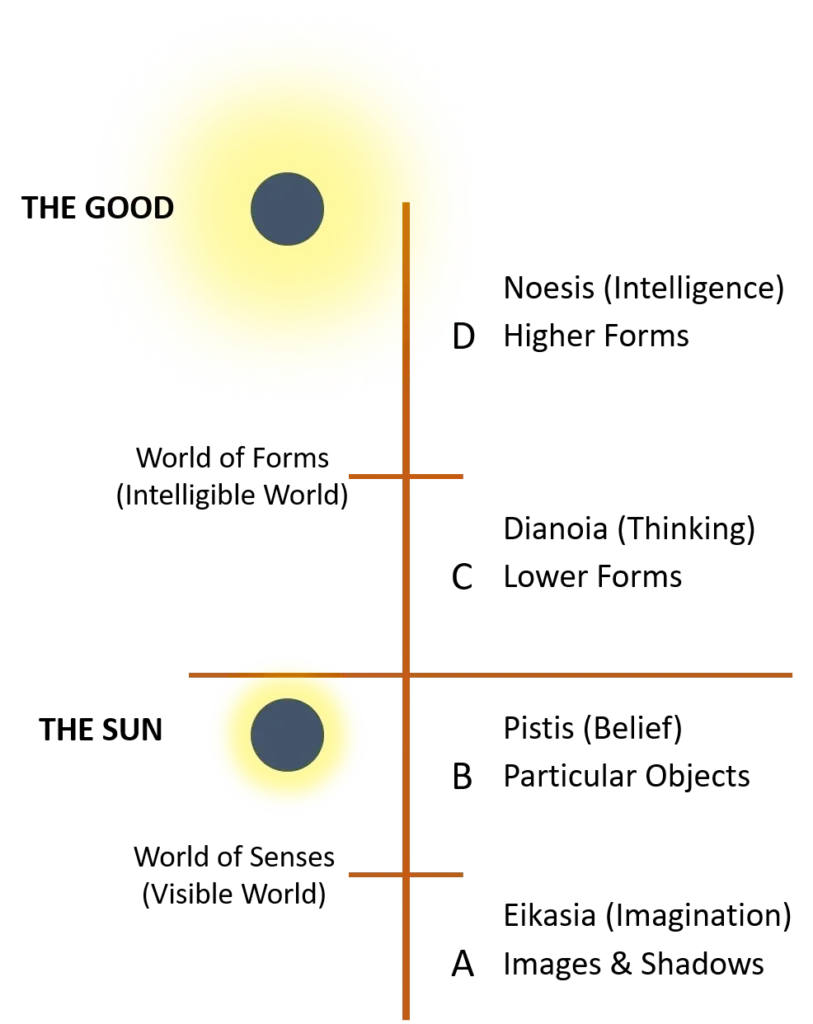

The Sun Analogy and the Form of the Good

- The highest point in Plato’s system is the first principle, which he calls the Form of the Good.

- Because this idea is very hard to explain, Plato uses an analogy called the Myth of the Sun.

- Although the Sun analogy appears before the Divided Line in the Republic, understanding the Divided Line first makes this metaphor easier to follow.

- When Glaucon asks Socrates to explain the Form of the Good, Socrates says he does not have complete knowledge of it.

- But after Glaucon insists, Socrates gives an example of something that resembles or is like a “child” of the Good.

- Socrates asks: We have eyes and objects, but what makes seeing possible?

- Glaucon answers: Light.

- Socrates explains that without light, our eyes cannot see and objects cannot show their colors.

- The source of this light is the Sun.

- In the physical world, the Sun makes objects visible and also gives our eyes the power to see them.

- This means both the seeing subject and the visible object depend on the Sun.

- Socrates then says: just as the Sun works in the physical world, the Form of the Good works in the world of forms.

- The Good makes the forms knowable and gives the mind the power to know them.

Summary

Plato uses the Sun analogy to explain the Form of the Good. Just as the Sun makes sight and visibility possible in the physical world, the Good makes understanding and knowledge possible in the world of forms. It is the ultimate source for both the mind and the objects of knowledge.

Three Ways the Sun Explains the Form of the Good

- Plato compares the Sun with the Form of the Good using three main points.

- Point 1: Making things understandable –

- The Sun makes physical objects visible.

- In the same way, the Form of the Good makes lower levels of knowledge intelligible (clear and understandable).

- Point 2: Affinity (similarity) –

- Our eyes have a natural ability to see only a small part of the Sun’s light spectrum.

- This shows a kind of affinity between the eyes and the Sun.

- Similarly, there is an affinity between the soul and the Good, which allows the soul to understand forms.

- Point 3: Creative and life-giving power –

- The Sun gives life to plants, animals, and humans; it warms, nourishes, and generates growth.

- In the same way, the Form of the Good is not lifeless; it is a creative and active source.

- This point influenced many religious thinkers, who connected the Good with the idea of God.

- In the visible world, the Sun is at the top, giving rise to objects, colors, nourishment, and even shadows.

- In the world of forms, the Form of the Good stands at the top, doing the same job at a higher, intellectual level.

Summary

Plato compares the Sun with the Form of the Good in three ways: both make things understandable, both have a natural link with the knower, and both act as creative sources. Just as the Sun is the highest point in the visible world, the Good is the highest point in the world of forms.

Why the Form of the Good Matters

- The Sun analogy helps us understand the nature of the Form of the Good, the highest reality in Plato’s system.

- For Plato, the Good is not lifeless or passive; it is active, meaningful, and deeply connected to human life.

- Humans are not only knowers; we also have social, political, ethical, and religious questions.

- Plato believes the highest reality must answer all these human questions, which is why he speaks about an affinity between the human soul and the ultimate reality.

- The highest form does more than give knowledge—it helps fulfill our needs for justice, beauty, and meaning.

- Understanding the Form of the Good is wisdom for Plato.

- To reach this wisdom, a person must rise from the lowest level to the highest level of the Divided Line.

- As we climb upward, the soul comes into closer contact with higher reality.

- Plato explains this whole journey with a mythological story because the idea is so deep that ordinary language is not enough.

- A myth is an imaginative re-creation that helps us “experience” something that cannot be expressed fully in words.

- When philosophy uses a myth, it signals that we have reached a very important point.

- To understand such myths, we need the right mindset:

- Take the story seriously,

- But do not take it literally.

- Myths do not give historical facts; they express eternal truths.

Summary

Plato uses myth to explain the Form of the Good because ordinary language cannot capture its depth. The Good is active, meaningful, and connected to human needs like justice and beauty. Understanding it is true wisdom, and myths help us imagine this highest reality in a non-literal but powerful way.

Beginning of the Cave Myth (Prisoners and Shadows)

(https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/

File:Allegory_of_the_Cave_blank.png)

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/legalcode

- Plato gives a dramatic myth in the Republic to show how the mind moves from the lowest level to the highest level of wisdom.

- Socrates asks Glaucon to imagine a long underground cave with an opening to the outside world.

- Inside the cave, at the deepest point, there are prisoners who have been chained there since childhood.

- Their hands, feet, and even their necks are fixed, so they can only look straight at the wall in front of them.

- Behind the prisoners, at some distance, there is a raised walkway and a fire burning behind that walkway.

- People walk along this walkway carrying different objects on their heads and talking to each other.

- Because of the fire, the objects these people carry cast shadows on the wall in front of the prisoners.

- The prisoners can see only the shadows, and they hear the echoes of the voices.

- They believe the shadows are real things, and they think the echoes come from the shadows themselves.

- Socrates describes this whole scene, and Glaucon finds the cave and the prisoners very strange, showing how limited their understanding is.

Summary

Plato begins the Cave Myth by imagining prisoners who see only shadows on a wall and believe those shadows are real. This setup shows the lowest stage of understanding, where people mistake appearances for truth.

The Prisoner’s Ascent Out of the Cave

- Socrates says: imagine one prisoner manages to free himself and turns his head around.

- His eyes hurt immediately because he has only ever seen shadows, and now he sees real objects and firelight.

- This shift matches the move from the first level (imagination) to the second level (belief) on the Divided Line.

- The bright fire confuses him, so he turns back to the shadows because they feel comfortable and familiar.

- Then someone pulls him upward, out of the cave toward the outside world.

- Outside, the sunlight is too strong, so he shuts his eyes at first.

- Slowly he adjusts and begins by seeing the shadows of trees on the ground.

- Next, he sees reflections in water, an indirect way of seeing real things. This matches the third level (thinking).

- Gradually he sees actual people, animals, and trees and realizes nothing in the cave was truly real.

- As his vision improves, he reaches the fourth level (intelligence) and begins to understand the real world directly.

- Finally, after several days, he looks at the sun itself and contemplates its nature.

- He understands that the sun is the source of everything he sees—light, growth, seasons, and life.

- At this point, he no longer needs shadows or reflections. He has direct contact with the highest reality.

Summary

The prisoner’s journey from darkness to sunlight mirrors the four stages of the Divided Line. He moves from shadows, to real objects, to indirect understanding, and finally to direct insight. Seeing the sun shows him the ultimate source of all reality.

Reaching the Highest Knowledge (The Form of the Good)

- When the freed prisoner reaches the highest point outside the cave, the sun he sees represents the Form of the Good.

- This is the first principle—once someone understands it, nothing higher remains to be known.

- All knowledge, all beauty, all justice, all goodness, and everything that exists ultimately comes from this source.

- The prisoner is amazed, but then remembers his earlier life in the cave—how people fought over shadows and believed shadows were real.

- Socrates asks Glaucon to imagine the man returning to the cave.

- When he goes back into darkness, he cannot see clearly at first. His companions still discuss shadows, but he can no longer see them properly.

- They would laugh at him and say the light outside has damaged his eyes.

- If he tried to free them and lead them upward, they might attack or even kill him.

- Plato is likely hinting at what happened to Socrates, who tried to lead people toward truth and was punished for it.

- Socrates then explains how this story matches the Divided Line:

- The cave represents the visible world.

- The fire inside the cave is like the sun of the visible world.

- The outside sun represents the Form of the Good in the intelligible world.

- The journey of the prisoner shows how the soul moves from ignorance to wisdom, from darkness to light.

- It also shows that wise people, after understanding truth, may still feel compassion and try to help others, even if those others resist or reject them.

Summary

The final part of the Cave Myth shows how a person reaches the highest knowledge—the Form of the Good—and how this wisdom transforms their view of life. It also shows the struggle of returning to help those still in ignorance, mirroring the soul’s journey from darkness to light.

Why Shadow-Based Understanding Is Not Real Knowledge

- Even by studying shadows, a person can create a simple, practical system.

- By watching the order and movement of shadows, one can form a kind of crude science based only on observation.

- This is like a local car mechanic who learns by experience which sound means which part is loose or how to make an engine start.

- His system is based only on trial and error, not on deeper reasons.

- This kind of understanding is empirical, meaning it comes only from experience.

- But Plato says this is not real knowledge, because real knowledge requires justification.

- True knowledge comes when someone understands the inner system—how the engine works, the principles of thermodynamics, combustion, fluid flow, and electrical circuits.

- Only when we know the reasons behind things can we call it knowledge.

Summary

From shadows and experience alone, we can form a basic, workable system, but it is not real knowledge. Real knowledge needs justification and an understanding of the deeper principles behind what we observe.

Turning Back Toward the Source (Critical Thinking)

- Socrates’ line about a prisoner turning his head backward is very meaningful.

- Looking backward means we stop focusing only on conclusions and instead examine the axioms behind them.

- This connects to the Divided Line: dialectic asks us to question assumptions before building further knowledge.

- A teacher’s real job is not to give you ready-made answers (shadows) but to point your eyes toward the light, toward understanding.

- Modern education often fills students with information and conclusions without helping them examine the foundations.

- True education moves in the opposite direction—it trains you to look for the source, not just the shadow.

- Most things we see in news, social media, and TV are just shadows, and people base their decisions on these appearances.

- A philosopher does more than learn ideas—they examine ideas and move beyond them.

- To do this, you need a critical, calm, alert, open, and questioning mind.

- If you accept everything blindly, you will never uncover truth. Philosophy is for those who search, question, and challenge.

- In the end, each person must decide whether they want to be a follower or a thinker.

Summary

This section explains that real understanding comes from questioning assumptions, not just accepting conclusions. True education guides the mind toward deeper truth, and philosophy requires a critical, active mindset that challenges shadows rather than blindly believing them.

Why the Wise Person Returns to the Cave

- A powerful part of the allegory is that a person who sees the sun and gains wisdom chooses to return to the cave to help others.

- Plato says humans are social beings; we live in a community, and real well-being is not just personal but collective.

- True wisdom includes concern for the good of everyone, not just oneself.

- But Plato also warns that this idea is dangerous.

- When you try to free someone from the cave or show them the light, they may attack you—just as people attacked and killed Socrates for trying to lead them toward truth.

- Yet Plato reminds us that when a Socrates is killed, a Plato is born—wisdom continues through new thinkers.

- Plato then raises an important question: if this process is so painful and difficult, why would anyone choose wisdom?

- Staying with shadows is easy; breaking free is hard.

- Wisdom requires leaving behind comfortable illusions and confronting your own beliefs and prejudices.

- It also demands a long, slow process of intellectual and moral effort.

- So why do it? Plato suggests that only those who deeply value truth and goodness will undertake this difficult journey.

Summary

This part of the allegory shows that the wise person returns to help others, even at personal risk. It also asks why anyone would choose the painful path toward wisdom. Plato’s answer is that truth, goodness, and the well-being of others motivate the philosopher to leave ignorance behind.

The Ladder of Love and the Search for Goodness

- Plato’s Symposium gives an important answer to why anyone chooses the hard path toward wisdom.

- In this dialogue, different friends share their ideas about love, and Socrates tells a story he learned from a wise woman named Diotima.

- According to Diotima, everyone is a lover—we all desire happiness, goodness, and beauty, and we want them forever.

- This desire, or love, is what motivates us to keep moving upward in life.

- Love may start with simple physical attraction, but it can grow into something deeper and more meaningful.

- Eventually, love can expand to include care for a group, for society, for peace, or for the whole world.

- Plato calls this upward journey the Ladder of Love.

- At the first step, we are attracted to someone’s physical beauty.

- Slowly we learn to value their personality, behavior, and intelligence, which are more lasting than physical looks.

- We discover that true beauty is not physical but something deeper and more abstract.

- In this way, love helps us rise from the visible world (physical beauty) to the intelligible world (inner beauty and qualities).

- As love expands, it goes beyond personal relationships and includes life, morality, justice, and the well-being of others.

- This love grows wider—toward humans, animals, and even the environment.

- Eventually, love guides us toward wisdom, virtue, spirituality, and philosophy, the highest levels of understanding.

Summary

The Symposium shows that love motivates us to climb upward toward goodness and wisdom. Starting from physical attraction, love expands to deeper beauty, moral concern, and finally to the highest philosophical understanding. Love is the force that pushes us from the visible world to the intelligible world.

Why the Highest Reality Is the Form of the Good

- For Plato, wisdom means seeing everything in the light of the forms, especially the highest form, which is the most beautiful and most good.

- This journey—from physical attraction to ultimate beauty—is the same journey as moving from shadows to the Form of the Good.

- In the Republic, Plato explains this path in a cognitive way (knowledge).

- In the Symposium, he explains the same path in an aesthetic way (beauty and love).

- For Plato, epistemology, ethics, and aesthetics are not separate fields—they meet at the same first principle.

- The Form of the Good is also the Form of Truth and the Form of Beauty.

- Plato believes that love is what motivates us to walk this long and difficult path toward the highest reality.

- Plato also asks: Why call the highest principle the Form of the Good? Why not some other name?

- The answer appears in the Phaedo, where Socrates discusses Anaxagoras.

- Socrates says that the ultimate cause behind everything can only be explained by the Good.

- Everything that exists or happens has meaning because it leads toward what is best or good.

- Socrates gives an example:

- Anaxagoras explains that Socrates sits in prison because of bones and muscles arranged in a certain way—this is a mechanical cause.

- But Socrates says this is not the real reason.

- He is in prison because Athens believed it was good for him to be there, and because he himself believed that not escaping was the good choice.

- The mechanical explanation is true but incomplete; it lacks purpose and meaning.

- Plato believes the ultimate cause is always connected to the highest good, not just physical necessity.

- So to understand reality, we must look beyond material causes and search for purpose, value, and meaning—all grounded in the Form of the Good.

Summary

Plato links wisdom, beauty, truth, and goodness to one highest principle—the Form of the Good. This form explains not only how things exist but why they exist and what purpose they serve. Understanding reality requires seeing beyond mechanical causes and recognizing the role of the highest good in all things.

Why the Divided Line Is Drawn Vertically

- Before ending, the lecture clarifies why the Divided Line is drawn vertically in this explanation, even though introductory books often show it horizontally.

- This difference does not change the meaning, but there are reasons for choosing the vertical form.

- In the Republic, Plato does not draw a diagram, but his language suggests a vertical line.

- He talks about the upper part and lower part of the line, which makes sense only if the line is vertical.

- Another reason is the length of the segments.

- Plato says the length of each segment reflects its clarity and degree of reality.

- The lowest level (shadows) has the least clarity, so its segment should be shorter.

- The highest level (direct knowledge of forms) has the most clarity and reality, so its segment should be longer.

- In many textbooks, this order is shown horizontally, but reading the Republic carefully suggests the vertical arrangement.

- The lecture follows Plato’s source text as closely as possible.

Summary

The Divided Line is drawn vertically because Plato’s description refers to upper and lower parts, and the length of each segment expresses clarity and reality. The lowest section is shortest, and the highest is longest, matching Plato’s original explanation.

Leave a Reply